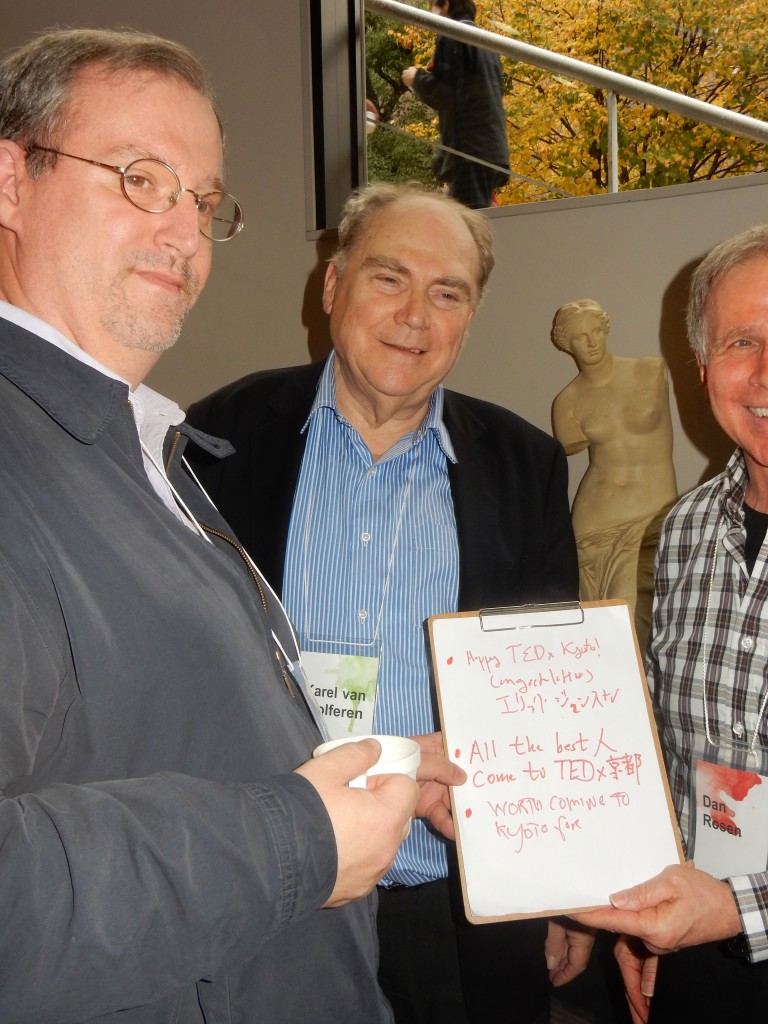

Eric Johnston of The Japan Times Osaka office offers some basic advice to writers seeking to get published in his newspaper and Japan-based publications in general.

Do you get a lot of inquiries from people seeking to get their work published in either your newspaper or other English-language media? If so, what kind of advice do you give?

I get what I’d say is a steady stream of inquiries, though a tiny fraction of what real editors in Tokyo receive. As to advice given or action taken, it varies depending upon my relationship with those doing the inquiring. Do I know them personally? A fair number of people who contact me are complete strangers. They saw my name somewhere and decided to drop me a line. In those cases, I rarely reply. Life is too short and I have my own work to do.

If I haven’t met them, but they’re a friend of a friend, and that friend has contacted me in advance to provide an introduction, I’ll usually reply to them – unless, by the time they get hold of me, a significant amount of time has elapsed. Please don’t write to me a month, or even a week, after your friend (who might also be my friend) introduced you. Why? Because I’ll assume you really don’t have any interest in contacting me, or that you’ve been spending the interim days (or weeks) getting rejected by other publications you really wanted to work with and now, shikata ga nai, you’re contacting me because there’s no one left.

But if it’s someone I’ve met, or someone I’ve already told to send me something, then, of course, I’ll look the submission over. Or, I’ll forward it to an editor and ask them to look at it. But I need to emphasize I have no authority to say yes or no to a writer. All I will do is make an introduction to the editors in charge, and a recommendation if I think the proposal is excellent.

What kinds of mistakes do people make when they send their initial story pitch?

First is a failure to display any form of professional courtesy. You’d be surprised at the number of total strangers who send direct and chummy, to the point of rude, e-mails, addressing me as if I’m their drinking buddy, college roommate, or “friend’’ on social media whom they can use emoji with instead of complete sentences. When it comes to initial correspondence, I’m very much a 20th century, pre-social media type. If you can’t write a polite, professional letter the old-fashioned way, regardless of age and experience, don’t bother writing because I can guarantee your e-mail will go into the trash.

The second mistake is that people often misspell my name. It’s “Eric Johnston’’. Not “Erik Johnston’’. Not “Eric Johnson’’. If my name is misspelled, the rest of your letter goes unread, and you’ll probably get a sharp reply if you try to get hold of me again. Nobody wants to hire a journalist who doesn’t take the time to do something as basic as check to see if the name is spelled correctly.

The third mistake is too many writers don’t research what articles the publication they’re approaching has run recently. Is your submission merely copying what appeared yesterday? I’ve upset not a few freelancers over the years because I sometimes quiz them, if they call directly, on whether my paper has run a related story at any time over the past month. If they can’t answer immediately, I hang up.

A fourth mistake is that when writers pitch a story, they can’t encapsulate the main points in two paragraphs. Some editors I’ve met demand that all writers summarize their story idea in one paragraph. So two paragraphs might be something of a luxury. Regardless, writers must always remember that they’re pitching a story to a busy editor who just doesn’t have time for long explanations.

Finally, there are those who cannot answer a basic question in their pitch: why is your story idea relevant to readers of that publication? Sure, the writer thinks it’s an important story and that readers of the publication will be interested. But the reality is that budgets are limited, and it’s hard if not impossible to justify spending money on a story that falls outside the publication’s editorial philosophy and—obviously—marketing strategy of the publication.

Common sense will, of course, prevent the above mistakes, or at least help minimize them. But as Will Rodgers once noted, common sense isn’t so common.

What about submissions in English from Japanese and non-native speakers?

Anything from a non-native speaker still has to be comprehensible, of course, and flow logically. But as long as the subject matter is interesting, relevant but unique, and well-researched, and as long as the work needed to correct the English grammar and spelling is minimal, most editors are happy to at least consider works from non-native speakers.

Personally, I don’t care if a story idea isn’t in English. Japan’s best freelance journalists cannot, or do not, write in English, only Japanese. If it’s really good journalism, I might translate a summary of the proposal and pass it along to an editor, who will hopefully engage a competent translator with media translation experience, as opposed to academic or commercial translation experience.

This isn’t always possible, but all intelligent and experienced editors and writers, regardless of their jobs and titles, recognize it’s better to engage a separate translator for a great Japanese-language journalism piece than to deal with submissions from an “eigo otaku’’ type who can go on for hours about Shakespeare or Hemingway and collects English language slang dictionaries, but has no idea how to tell a story. Or, worse, something from pedantic translator types who, to put it in musical terms, play all of the notes exactly as written, and yet sound absolutely horrible because. . .they’re playing all of the notes exactly as written. That’s why people with good musical sense often make the best journalists.

To learn more about Eric Johnston and his writing interests, please see here for his earlier piece on being a news reporter.