1.

Not far from the American Embassy in Havana, mere steps from the body of water that proves narrower than ideology, stands a monument to the USS Maine, which exploded under mysterious circumstances in the city harbor over 100 years ago. Upon the monument an American eagle once perched, until on a January day in 1961 its head was carried away by citizens equally carried away by revolutionary fervor.

It is easy to lose one’s head over Havana. Travelers return from the city raving about the classic automobiles passing beneath old colonial period buildings. Like most visitors, it was the cars that held the most appeal to me. I’d first heard of them twenty years ago, over beers in Hanoi with an American whose boat had engine trouble, and was forced to dock in Havana for a few days for repairs. So it was only fitting that one of these old automobiles was the centerpiece of one of my first views of the country, spied from a plane high above the open fields, as if I were reenacting the final scene of American Graffiti.

Here the American graffiti is the island’s relationship with its neighbor to the north, writ large upon every aspect of Cuban society. The half-century long trade embargo had seemingly stopped the clock in 1960. More accurately, every so often somebody keeps turning the hands back.

There are few places on earth so stuck in time, a concept that has admittedly become a travel agent’s cliché. They’ll tell you to go immediately, before the old is lost forever. But how much more exciting to visit a place in the midst of change, as the traveler comes back less with the static memory of wandering a picture postcard, and more with the feeling of having connected with the flow of history.

I couldn’t have timed my visit better. A week before I arrived, the first commercial flight in over half a century arrived from the US. It landed just days after the death of Fidel Castro, who in taking control of Cuba in 1959 had caused those once regular flights to cease in the first place.

I’d booked my own ticket ten months before, not anticipating any of these events. The visa situation at that time called for a round-about approach, so I opted for a couple of days on the beaches of Cancun on either end of the journey, which admittedly wasn’t such a hardship.

José Martí Airport has a certain Third World vibe, and I smile at the irony of its 19th Century namesake having initiated the propulsion of Cuba toward the First. I catch a faint whiff of cigar smoke the moment I exit the plane. Bodies move noisily and chaotically through the hot, still air. A father carries a shirtless child, limp and listless in his arms. He is waved over to a table, which I presume is staffed by the quarantine squad. I think of ZIKA and suddenly worry about the poor kid. Behind me a few pieces of luggage from our flight begin their turn on the carousel. For some unexplained reason, no other bags will appear for the next 90 minutes.

We arrive finally at our hotel, the plaza in front looking like a car lot circa 1958, filled with monsters of Detroit-made steel. Many of these beasts are now used as taxis, mainly for foreign tourists willing to pay the high fares.

I’m not given much time to admire them as we are quickly shuffled over to the old town. Habana Vieja is pedestrian friendly, and in the fading light, clusters of silhouettes move along the stone streets before 16th Century facades. Most of the action seems to be up a single shallow alley where a half dozen restaurants are crammed, their sidewalk tables filled with boisterous foreigners high on rum and the easy Latin vibe.

We take our dinner in the far corner of the alley, inside Paladar Dona Eutimia, which appears to be an old home tricked out to serve meals. So begins our introduction to Cuban service: slow, patient, unhurried. This allows time for conversation, as well as drink, for that is the only element of the Cuban meal that arrives quickly. When it arrives, the food is heavy and rich, and goes well with red wine, Chileans having cornered that market. From the very first, I fall in love with Cuban cuisine, a love consummated on this particular night with ropa vieja, shredded beef in a chili, tomato, onion and cumin sauce. I am lucky to be traveling with other foodies, and the four of us are generous with our orders, rotating our plates every so often as if we are speed dating. Well sated, we limit our selves to just two desserts.

After dinner we step into the neighboring Taller Experimental de Grafica gallery to admire the prints, having little context for Cuban art beyond that obsequious photo of Che. Tired as we are from the travel, tonight is not the night to learn, so we step out before long, and pass the al fresco diners taking the night to the next level. One table is unmistakably Russian. I am tempted to say hello, but press on toward the car.

It is a missed opportunity of sorts, for Russia, then the Soviet Union, was the one foreign country besides the US to have any regular interaction with Cuba over the years, though those relationships were polar opposite in nature. So I am curious as to how the average Russian views Cuba, its vassal state of sorts, once a red flag to fly in the face of its long-term adversary.

2.

Second hand contact with a people through books or film can most certainly be informative, but one accepts these insights with some risk, filtered as they are through whatever baggage the writer brings to the project. Far preferable to get out amongst the people and observe directly. On this first full day we are to do just that, but with a twist. We step out of the hotel and straight into a horse-drawn carriage. My girlfriend and I hadn’t known about this, and agree that this isn’t our thing at all, but still we take the ride. And so it was we began our spin around the city center, seated in the privileged position of the well-heeled colonist, looking down on our subjects.

The city itself takes revenge, the cars spewing choking exhaust. Eyes and throat rebel as the unfiltered petrol enters our systems and does some colonizing of its own. But in time, the beauty of Havana works as a remedy. The first wave of travel books written after the revolution all talk of the city’s crumbling beauty, but by 2016 an obvious attempt has been made to clean things up. In most cases around the world, this restoration is done by wealthy foreigners who have bought properties. But in Cuba, this has yet to begin on a large scale, as investors cautiously negotiate Cuban law, and it wasn’t until very recently that Cubans themselves could own their own home. As it is, all properties for sale have already been renovated, and despite passing a great number of these obviously empty buildings, the streets below are bustling filled with locals just going about their day, still somewhat oblivious to a pair horse-drawn carriages pulling past, their occupants wearing sunglasses and trying not to breathe.

We wheel through El Barrio Chino, which has only a handful of Chinese anymore, with nary a dragon to be seen, nor the color red. To me, the architecture that most impresses is the French Baroque, which adds nice flourishes to the Spanish colonial which it dwarfs. The gem of them all is the Capital Building, modeled on the dome of its twin in DC. And of course, old Detroit classics line every street, and on every other street stands one broken down, hood open. The dull hum emitting from those that do run hint at a horsepower far greater than that which bears us. Still, the cadence of the hooves is hypnotic, and as they carry us to the next destination, they take on the sound of boots on the march.

I had been looking forward to visiting the Museo de la Revolution, since I am intrigued by the absurd superlatives of propaganda and the glorious monuments they spawn. With Cuba’s proximity to its greatest enemy, I was expecting the heights I’d seen in a similar museum in Hanoi, with its photographs of dead children and jars containing fetuses twisted by Agent Orange. But this one is somewhat subdued, with near empty rooms displaying a few photos and jungle-tattered clothing and equipment. It is as if the success of the revolution spoke for itself. The structure that houses it had once been Batista’s Presidential Palace, and from its design you can see the former dictator had a Versailles fetish, if Versailles had been designed by Tiffany’s. Today, the famous ballroom is playing host to a party of generals who have gathered along with Minister of Defense, who politely declines my friend’s request to be included in a photo. Who knows to what purpose such a photo might be used?

Our horses draw their rest at Habana Vieja, and we are let down to wander its stone covered streets. This is of course Havana’s real treasure, and its carefully planned restoration project has earned it a UNESCO rating, not to mention hundreds of tourists. Despite this latter fact, there is no begging, nor any pushy touts. The biggest danger I’m told is getting bullied into taking a photo with the cigar-chomping women who look as if they just stepped off a Chaquita banana label. Thus we go unmolested through this veritable architectural museum, popping into the odd museum and café, perusing the photos of Hemingway inside the Hotel Ambos Mundos, where Papa is said to have written For Whom the Bell Tolls. The street before the Plaza d’ Armes is laid with wood, used at one time to soften the sound of horses’ hooves. Along this stretch dozens of book stalls, each one busy and a testament to Cuba’s high literacy rate. Upon the covers of many of these can be seen one of the Bearded Trio – Castro, Che, Hemingway. As I lean in to have a look at one stall, its owner begins a chat and by its conclusion I’ve bought an old peso coin that bears the face of Che, who I’ve been told I resemble somewhat (sans beard). The coin is worthless I know, but the dollar that I’ve given in exchange I see not as a scam but as a tip for an interesting encounter.

Our walk ends not far away, at the Plaza de San Francisco de Asis. The former church that gives the square its name is known for its remarkable acoustics and is now the setting for frequent concerts. I am lucky to find a choral group at practice inside, and I stand mesmerized as the voice of one soloist traces the curves of the arched ceilings and the grooves of the pillars holding them up.

We have lunch adjacent, in the Café del Oriente. The wooden bar, checkerboard tile floors, and deeply varnished tables simultaneously harken both 1950s New York and 1920s Paris. A pianist visits both these periods with music that acts as a sort of flavor enhancer for yet another stunning meal.

The wine has made me drowsy, and the thought of wandering through a market has no appeal. While the other half our quartet shops, my girlfriend and I go in search of coffee, which we find in a converted warehouse down on a pier somewhere. To my delight I also find local craft beer. Some of the other tables are drinking theirs from long yard glasses, and as they tip them skyward, it looks as if they are part of the horn section of the band creating heat on the stage. The vocalist gyrates somehow in a dress three sizes too small, and somehow the horn section behind her isn’t distracted as they start and stop their parts on a dime. This is my first encounter with Cuban music proper, and as has been oft-told, what has been caught on recordings is only part of the story. (And during my time in Cuba, I never saw any musician that wasn’t of the highest talent.) It is hard to tear ourselves away, but it is time to dance.

On approach the street looked like a quiet residential street, and Casa del Son is discreetly located midblock. This former house has a half dozen rooms converted to studios, each lined with mirrors and hung with bright and colorful artwork. We pass through the gyrating bodies of the entry room, and are led through its open-air labyrinthian corridors to a room in back.

For the next 90 minutes we are led through our paces by a small wiry man with a head shaved but for a lone patch at the pate, from which extends a stump of pony tail. His tank top, quickness of speech, and hurky-jerky movement seems copped from the hipster streets of New York (though no doubt the reverse is more apt). But man can he move! Salsa isn’t such a difficult dance to learn, being little more than a quickened boxstep. More than the footwork, the spirit of the dance is in the hips. The movement is an invitation, a promise. It is a dance to be danced with one you love, even if that love lasts a single night. As it is, my own love is being twirled in the arms of another, and I am paired with a young woman whose eyes, and thoughts, are far away. Still, there is never a bad time to dance, and I spring rather than walk back toward the front door at the end of the lesson, body drenched in sweat which flows toward the earth to which I now feel far more connected.

We welcome the evening with drinks out on the terrace of the Hotel Nacional. The drink in my hand is lost on me, this libation of the liberation, this Cuba Libre. The well-known, fancy moniker doesn’t change the fact that it is simply a rum and coke, the drink of high schoolers, a sip of which conjures up the ghost of hangovers past. We sit here awhile, watching the sun lower itself over toward the Yucatan. On the near empty stretch of the Malecon below, a horse carriage moves in the same direction, followed by an old Buick, then a red Chinese-built tour bus. Bigger, faster airborne vehicles have just begun their passage across these waters before me, and with their coming, such quiet scenes are certain to cease. I ponder the inevitable, as I empty the remainder of my drink onto the grass.

3.

The Caribbean is renowned for its easy, laid back nature, but Cubans take it to another extreme, raised as they are on long queues and systematic uncertainty. If patience is a virtue, then Cubans must all be saints. The only time I ever see anyone move beyond an amble is the morning it rains. But even then they move only negligibly faster.

This is the day we were meant to commence our drive by heading along the Malecon, then on through Miramar with its big houses, former estates converted to embassies. But our guide G tells us that we need to take an alternate route, as the Malecon would be flooded by now with storm-born waves. Instead we navigate the grander boulevards of the city, but even many of these are flooded due to the poor drainage system, the old cars stranded like dinosaurs in a tar pit. Within, the passengers sit quietly in wait.

Free of the city, we move quickly but cautiously along the broad, well-cared for Autopista, heading west. Even behind the wheel, no one seems in much of a hurry. The rain and clouds begin to lift, revealing a flat land, unkept and shrubby. It is surprising to see an almost desert-like quality to a Caribbean island. The hills begin to rise, but there is little else on the landscape. There appear to be fewer old cars in countryside, but then again, there are fewer cars period. Here and there, somebody is standing alongside the road with his hand in the air, clenching cash. Road-trippers in Cuba act as impromptu taxis, and can pick up money for petrol by offering rides. A lucrative act of charity, as many cars are packed six to eight in a vehicle.

The landscape of Valles de Vinales truly impresses, its perimeter lined with tall and fragile limestone hills, pocked with caves. We are shown one cliff face painted with colorful fossils, dinosaurs and prehistoric men. Cats doze in the grass beneath, and we are offered rum in a small thatch hut nearby. (Every destination on our tour seems to include a rum drink.) There is more rum at our lunch stop, in a nameless restaurant alongside the highway. The owner appears to be quite a character, entertaining a group of people with some uproarious tale. We are not invited, which is just as well, allowing us to enjoy a quiet lunch alone with the scenery. Eventually one of the guys comes out of the kitchen with a guitar, and leads into some of the better-known Cuban classics. He seems to like my voice as I spontaneously join him on Guantanamera, so he hands me a pair of maracas. This soloist then promptly becomes part of a duet, and I enjoy helping him finish his set. It is a reminder that in Cuba, music will always trump politics.

My favorite cultures are those that are the most musical, that find value in time dedicated to music. In the sweep of the rat-race, it is difficult to find time to pick up a guitar. And Vinales represents this, a place where traffic moves at the pace of a horse’s tail. Pony carts ferry people past rows of bungalows, each with wide porches and brightly colored rocking chairs. This is the greatest resource of the valley, the scenery, and the rocking elliptical flow of the day.

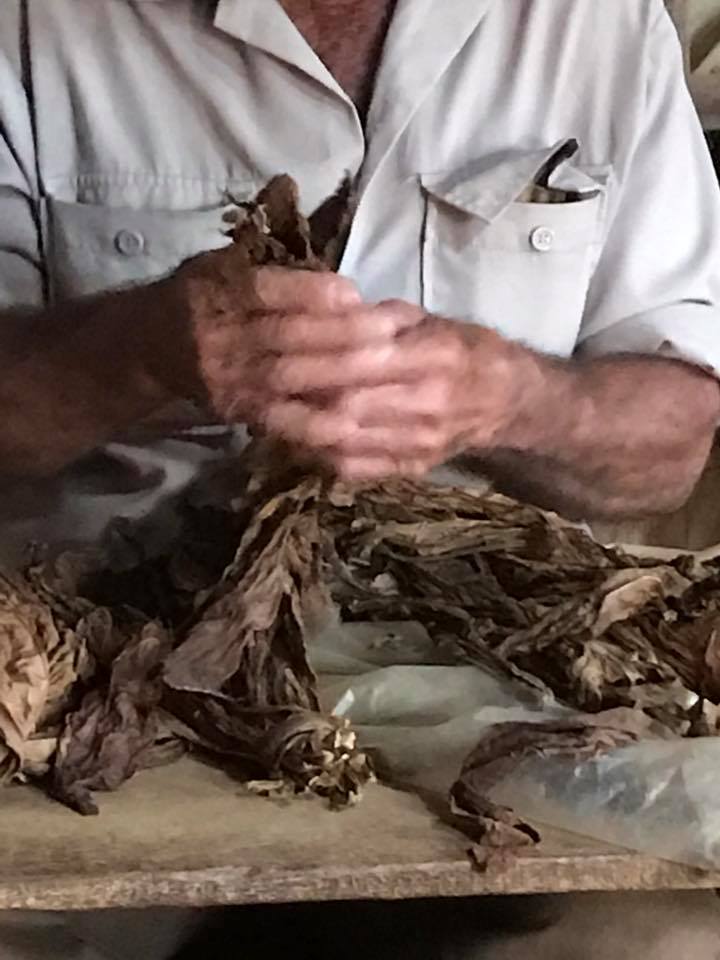

The only thing missing then, I suppose would be a cigar. Our guide G takes us to a small farm on the edge of town, where we watch a man roll his leaves with his tobacco tanned hands. He must have rolled hundred of thousands in his life, and there is a precision there that is beyond thought, relying more on habit and muscle memory. His boss has a similar relaxed nature, though more methodical in his jokey charm. He has us all laughing before long, and we are sad to decline his offer to stay a night here at his farm. Sadly we need betray the spirit of the Valley, for we have appointments back in Havana.

The first of these is dinner at La Esperanza, renowned as a gourmet delight. The owner meets us at the door, charming and gracious, but apologetic. It seems that there is a film team from New York filming a documentary, and their lights, cables, and equipment are strewn everywhere. We say that we don’t mind the chaos, and take a table adjacent to the patio. (The patio itself would be ideal, but it has started raining again.) The occupants of the only other occupied table are going through the motions of a meal, as the cameras circulate around them, and the boom mike hangs threateningly above. Besides the TV presenter, the diners include a member of Buena Vista Social Club, Cuba’s premier ballerina , and the man heading the restoration of Habana Vieja. When the shooting stops, all begin to mill about, and the night takes on the feel of a party. We too are swept along, and I spend a fair amount of time with the producer, hearing tales of what it had been like to shoot during Castro’s mourning period. Having previously received governmental permission, they were able to get near unlimited access. It is a good night, albeit a surreal one. But there is another destination to come.

The Tropicana fulfills all my dreams of visiting a time when travel was glamorous, when it was unheard of to go anywhere without a dinner jacket in your valise. Granted I am tie-less in my linen sport coat, but the spirit still applied. The club is in what appears to be a distant suburb, up a tree-lined drive well hidden from the road. The hostess hands me a fat Cohiba and leads us to our table down front of the stage. The tables behind us are filled with foreign tour groups, all tinted blue when seen through the haze of cigar smoke. A trio of waitresses come up and plonk down a metal ice bucket, a bottle of rum, and four colas. I ignore the rum and instead drink the soda. It is the local brand of course, due to the embargo. (The only Coca Cola I see in Cuba is in the neutral land of the airport bar.) I like this about Cuba that the usual brands and logos are nowhere to be seen, a little corner of the world where corporations don’t yet dominate. How long till Coke signs permeate the walls? How long till the rum is American?

The show starts promptly at 10 pm. A bevy of sequin-draped beauties wrapped in ostrich plumes fill the stage, the aisles, the dance spaces high above. There is a phantasmic quality to the night, in the sweep and flash of colored light, tricking the eye into thinking it is observing a bizarre species of animal. They way they completely surround us is quite unnerving. They are joined eventually by young men in their white suits who whip and whirl and pump their hips. Ricky Ricardo never did anything like this. Over the night the costumes shift into the more and more bizarre, the hats and frills getting bigger, then falling away completely to be replaced by gold-lame bikinis that help keep a portion of the audience awake. The men are bare chested and muscled, which wakes up the rest. The music stays high energy, foot-tapping, though growing a tad monotonous. It will go on through the night but will do so without us. I grab my girlfriend’s hand and twirl and dance her from our seats and up the aisle, like we are part of the show. We laugh as we escape into the quiet open air, swept clean by the winds blowing through the hedges, as if fanned by a flock of ostriches.

4.

Lost in Havana. It sounds like the title of a spy novel, but it is true. We had simply gone to the winding spiral of an underground passage to the hotel annex for breakfast, and somehow, hadn’t been able to find our way back. At some point we give up and escape out a broad glass door, then try to get our bearings. Decades of decay are being removed from along an entire block, soon to be renovated into a massive hotel that promises luxury, and hopefully, better signage. On the street below, a good number of foreigners, Americans mostly, are all walking in the same direction, and in following them, we arrive back at the front of the hotel.

I am surprised by all those Americans but really shouldn’t be considering the recent opening of legitimate flights from the States. They all seem to be staying at my hotel, and that morning, they clog the lobby as if all the tour groups are leaving at the same time, to board a fleet of buses that blockades the boulevard in front. The hotel is a popular spot, and at happy hour, the lobby is filled with people drinking wine or overpriced rum drinks, the men being men with their cigars. It is fun on an American scale, scripted fun, with little of the relaxed looseness and spontaneity of the Cubans. Still, it is an interesting glimpse of how things must have been before the Revolution, all these moneyed notreamericanos gone south to let down their hair. If all stays the same, this will only increase.

We begin our day on the outskirts of town at the home of a man who truly did know how to party. Hemingway’s Finca la Vigla sits somewhat unobtrusively atop a tree-covered hill that overlooks the sea. I could see why the writer loved this place, and how in losing it he had lost more than just a home. He was apparently quite untethered after forfeiting this refuge, and just a year later found a refuge far more permanent.

The house appears to look as it had the day he left. Visitors aren’t permitted to enter, but we are able to see the interior well due to the copious windows in every room. I am most taken with the books, which fill every wall of every room. As I squint and lean to take in the titles, I feel a tap on my shoulder and see it is the producer that I’d met the night before. He’d gotten filming permission all over the island, but hadn’t been able to receive it here. He told me that he wished I’d turned up just 10 minutes earlier, wielding my writing credentials and a tall tale that I was working on a piece for a major US newspaper. (I was flattered, but who did this guy think I was, Hemingway himself?)

Two women sit by the pool and chit-chat. These guards aren’t particularly concerned with people fiddling with Hemingway’s famed boat Pilar, which has found permanent dry-dock atop the tennis court. This is a nation seemingly taken with boats, as across town, the Gramma, which brought Castro home to wage revolution, stands under glass, beneath the gaze of 24-hour armed security. Both boats seem in far better condition than the handful I’d seen in Havana harbor, wrecks purposely hobbled in order to discourage trips of a longer nature. In Hemingway’s case, his final flight took him beyond America, beyond fame, to immortality.

Heading east, our own road is again relatively untraveled, and dotted on occasion with those trying to flag a ride. At one point a wall rises up, running parallel to the highway for thirty-three kilometers. It was built for no other purpose than to dispose of the stones that had been plowed up when farmers were laying out beds for sugarcane a century ago. Today not a thing has been planted, which surprises, as Cuba has the ideal climate to grow nearly anything. The problem appears to be in the organization of these state owned farms, which hadn’t even been utilized during the near-starvation years of the Special Period after the fall of the Soviet Union, Cuba’s biggest benefactor.

We divert off the highway not far past the turnoff to the village of Australia, which besides being an amusing moniker had been Castro’s base during the Bay of Pigs. Along this narrow road we begin to see crops, rows upon rows of corn, the rough stubble of tobacco. Growing amongst them are signs bearing political slogans, and the faces of Castro and Che begin to pop up like mileage markers. They are proud of the revolution in the country, and few places more than Cianfuegos, our next stop. The town is prettily arranged along the curve of a long bay, and far across the waters stands the abandoned hulk of an unfinished nuclear power station once planned by the Soviets.

Our first task is to fuel up with lunch at Paladar Ache, yet another tidy house wrapped around a lovely garden. Masks hang along one of the walls, each representing a Orichá, a Santeria deity disguised as a Catholic saint. The two religions have over the centuries been fused and intertwined, and in the few cases that I encounter Santeria I am reminded of the folksy nature of Catholicism of rural New Mexico.

Fusion becomes the theme of the day, not only in the meal served up, but in the look of the buildings about town, a mish-mash of various European cultures and styles, all tempered by a mild Caribbean climate. The most extreme example is the Palacio de Valle, which upon approach looks typically French, yet whose roof has been capped with a Mughal palace.

My favorite building is the Tomas Terry theatre, and I’m not alone in my devotion as it had once attracted the likes of Enrico Caruso and Sarah Bernhardt. I sit in one of its plush red seats, watching a dance troupe practice for the weekend show. From here we stroll the French renaissance plaza ringed with even more beauties, and up to the Paseo del Prado, punctuated midway by a statue of Benny More. The statue is modest, yet few legends of Cuban music were as big as Benny. Down a pair of side streets is a small street market, with a few dozen stalls catering to the localized crowd of Saturday strollers. It had a charm shared with other markets I’d seen in other socialist states, a timeless look at capitalism reduced to a neighborhood scale.

5.

The historic towns of Cianfuegos and Trinidad have been forever paired by UNESCO as heritage sites, but they each have their own distinct character. The former is typically Caribbean in that it is (slowly) facing the future, yet not at the expense of its rich colonial past. Trinidad on the other hand appears happy right where it is, which is 19th Century Spain. Renowned tourist sites can be divided into micro and macro types. Kyoto, where I live, is the former, being essentially an ugly city filled with some marvelous sites. Trinidad is the latter, for the town itself is a gem. Nested on a long rolling series of hills between the mountains and the sea, it is a spiderweb of little lanes, cobbled with what I’ve heard best described as turtle-shells, and sloping downward toward drainages running down the center. These irregular surfaces make for difficult walking, slowing everyone to a leisurely amble. Those who can’t even be bothered to walk sit before low two-story buildings painted an array of hues, and punctuated with brightly colored doors. When the pony-drawn carriage before you passes by a parked 1952 Chevy, you suddenly find yourself part of a travel brochure.

Like in all the best towns, there is little to do but absorb the vibe. We listlessly explore a couple of palazzo museums, poke our heads into churches. Have the obligatory canchanchara at its namesake Taverna. I also take the time to do a solo walk at dawn one morning, into the barrios well away from the tourist heart of town, where young dudes work on their motorcycles, and groups of young girls stroll to school in their uniforms. Along the way I come across a Yoruba temple, in the courtyard of which a man is washing and plucking a chicken, either a result of, or preparation for, a ceremony of some kind.

The slow pace of life in the daytime serves to pace the locals for their revelries at night. Music is simply everywhere, in every café, spilling onto the streets. Not far from the steps beside the Iglesia Parroquial where tourists sit and welcome the night, we dine at Paladar 1514, an antique shop of sorts crammed with the wares of five centuries. This all adds to the restaurant’s ramshackle look, of crumbled brick and absent roof. I believe that the structure actually is half-collapsed, but we dine alfresco safely between two columns. Our waiter is a very young man who’s been working there for just a few weeks, and he deftly avoids our queries about history in charming and amusing ways. We are the only diners at first, but slowly others come to sit at tables overladen with ancient ceramic and glass (removed of course before the meal arrives). Another waitress comes on duty, moving through the narrow spaces as if dancing tango; all the movement below the waist. At some point musicians crowd into one corner of the courtyard, and before long I am pulled before them to dance with a young black woman that I’d seen flirting earlier with the mulatto bartender. Trinidad has a certain racial ambiguity, its people even a greater array of colors than its buildings, yet seemingly devoid of any of the usual tension. When I make this comment to my guide she tells me that Trinidad’s port had been one of the points of entry for African slaves. In fact, more African slaves arrived in Cuba than the United States. This is mainly because the Americans saw the value in have healthy slaves to work and breed. The Spanish simply worked theirs to death, to be replaced by new African slaves. Things have improved of course, but G tells me that the lighter-skinned tend to do better with education and employment, but the overt racism of the North is quite rare.

The final morning we drive out to the Sierra del Escambray, tracing the coastline lined with small, underdeveloped hotels before turning inland to climb and wind over the tendrils of hills pointing seaward. Roads like these never fail to amuse. It is as if there was no time or thought about grading. Far easier to just pave the hillsides, creating a roller coaster effect. Always thrilling, always exhilarating.

We stop at the park information center which has detailed information about the various hikes in the area. Towering just above is a large hotel block that had once been a TB sanitarium. We leave this soon enough, in the back of a massive Soviet-built troop transport, bouncing along on the hard bench-like seats as the truck powers along the windy mountain roads. Now and then small settlements appear, small clusters of squat homes amidst all the verdant green. Symbols and slogans of the revolution are everywhere, little wonder since that these hills were home to the revolutionaries for much of its struggle.

We climb from the truck in a small village at the start of the trail., and quickly come across a decent-sized coffee plantation, shaded by massive trees. This canopy shades us as well, as we make our way gingerly along slopes made slippery from the recent rains. We come eventually to a tall waterfall, and a swimming hole that on this day serves as playground to a handful of foreigners.

The second part of the hike isn’t much harder than the first, though it does require us to climb gradually from the valley. The views open up some and include the river we parallel, which in itself draws out more bird and wildlife. We leave the jungle at a small farm, not far from a series of bungalows where we’ll lunch. We sit out on the veranda, eating a plate of chicken and the obligatory beans and rice. It is a pleasant, bucolic afternoon, though now growing hot. When it is time to depart, our truck is nowhere to be found, so we sit awhile more in the shade, watching the chickens who, no matter how fast they can run, cannot outrun their destiny as tomorrow’s lunch.

Back finally at our van, for the long ride to the airport. Our guide G decides to pass the time in discussing Cuba and what it is like to live there. For days we have politely avoided the topic of politics; it seems as if she finds it important to show how politics is intricately entangled with daily life.

She tells us of the hardships of the Special Period, the country in free-fall after the collapse of the USSR, its main economic trading partner. The government did a remarkable job in strategically weathering out the crisis. Not to say that the people didn’t suffer. Food production dramatically declined, due to the absence of fossil fuels. But the Cubans are a clever people, due to a high level of education and resilient due to the embargo. Bicycles began to appear on the streets, and many moved out into the countryside to grow their own food. The diets became incredibly imaginative and innovative, with people substituting plantain peels for beef, and utilizing vegetables long overlooked. One bizarre side effect was the huge reduction of deaths from as diabetes and heart disease.

Cuba weathered this, as they weathered everything else. But with exposure to tourists growing exponentially, Cubans are beginning to resent the stagnation of their island. Most live on a monthly salary of $25 dollars a month, and I know that some of our meals cost more. Yet despite this, she, along with all the other Cubans I met, truly love their country and have no intention to leave. And therein lies the paradox. To wait as patiently as the Cubans do, implies the belief that something better will come along. And after fifty plus years, at no time does the future look brighter than it does now. Obama seemed determined that part of his legacy be to open up the country, and I smile at the thought that the “Hope” slogan of his initial presidential campaign also holds meaning for the people of this nation. Granted his successor seems equally determined to slam shut the doors again. Yet a bigger factor is the fact that Cuba is taking its first baby steps into a future without Fidel. It is hard to picture a Cuba without Castro, despite the fact that the Cuban exiles in Miami and the CIA have been doing that for decades. But the issue all along was with Fidel, and never with the Cuban people.

So that hope stills exists. Americans and their tourist dollars are now flowing in, and that will certainly change things. It won’t be long before the big corporate players follow, and familiar logos will begin to appear on Havana’s crumbling facades. Perhaps one of those logos might even be of a certain hotel chain owned by Obama’s successor himself.

Personally I think that Cuba’s biggest potential lies in being a major destination for medical tourism. This island is famous for the high quality of its healthcare system, and it exports more trained medical personnel to the developing world than all the G8 countries combined. Americans are already finding inexpensive treatment in countries like Thailand, India, and Singapore, and it won’t be long before they find relief closer to home.

At any rate, the tourist industry is a young one. I notice that there is a definitive separation between the Cubans and the tourists who are beginning to move amongst them in greater and greater numbers. It’s unlike other cities I’ve been, where there’s much more engagement, more interaction. Here, the Cubans continue to go about their business, or their lack of business, as the touts are as yet unpushy, choosing to let these specimens of overseas wealth simply drift by That ability to choose implies a freedom that they’ve had all along. Let’s hope they can weather the myriad of choices to be made as their island grows more and more open.

The inevitable return of the big hotels and international conglomerates may return Cuba to a role similar to that it had in 1959; that is, a tourist vassal state, with all the familiar abuses. A more optimistic view is that Cubans, being proud, patient, and educated people, will take a slower more sensible approach to things. But the people are most certainly hungry. Not for food this time, but a chance to share their strengths with the rest of the world.