Now celebrating its 30th year, Kyoto Journal is about to return to print with KJ 89, after a sojourn of 13 diverse issues in the not-quite-parallel universe of digital format. With this issue we will shift from quarterly to biannual publication, supported by more frequent postings at kyotojournal.org.

Why go so determinedly retro, in today’s ever-accelerating never-sleeping instantly-available 24/7 globalized info-environment?

Exactly! —What we would prefer to offer is an antidote to that kind of frenicity.

The digital experience is seldom memorable, however novel its design; it lacks presence, too easily dissipates into the background blur of electronic media that occupies the user’s ever-decreasing attention span. On the other hand, a physical magazine (or book) prompts you to find relatively undistracted time for it. Opening physical pages, breathing in the distinctive aroma of ink and paper, you refocus, entering a different mental space that’s more conducive to engagement with fresh ideas, to perceiving lateral connections and subtle resonances.

There’s a sense of singularity and authenticity in that process, that goes a long way back. Witness the enthusiasm of third-century Chinese poet Fu Xian, in his Paper Ode, making the first known reference to how new-fangled mulberry-bark paper was replacing bamboo strips:

When the world is simple, embellishment has its uses. The rites and materials change as time goes by. As for making records, carvings replaced rope knots and bamboo was replaced by paper. As a material, paper is fine and worth cherishing, for its shape is square, its colour is pure and its nature is simple. Articles and expressive words are carried on its surface. It unfolds when I want to read it and I can fold it up again when I am finished. If you are living away from your family and relations, you can quickly write a letter and send it with messengers. No matter how distant your hearer, your thoughts can be expressed on a sheet of paper.

[Quoted in The Paper Trail: an Unexpected History of the World’s Greatest Invention, by Alexander Monro]

Of course, publishing in the form of 21st century binary-coded photons offers additional attractive benefits: freedom to expand content without being restricted to multiples of 16 physical pages, for a start; immediacy of direct release via effortless distribution (virtually cost-free); freedom to correct embarrassing typos etc, post-release; potential to incorporate videos, animations, live links… Not to mention the slick out-there cool factor; also, not needing high-maintenance humidity-free storage space for stacks of back issues in a benefactor’s basement during Kyoto summer…

Associate Editor Lucinda Cowing, our marketing strategist, says print is back. “Basically the majority of those currently subscribed or who know us want KJ in print, and many comment that the digital version is less enjoyable to read. Also, independent publications that overlap genres (like KJ does) have grown in number and in circulation over the past few years (Kinfolk can be credited for starting this trend, I think—they often sell a lifestyle/ideal, revolving around living simply, taking time to read and appreciate handmade things, etc). I would go so far as to call this movement a backlash against digital media now, because according to recent statistics even major US newspapers seem to still maintain a larger print readership than digital.”

Another market factor identified by Lucinda: “There is huge interest in Japan—the tourism boom aside, we see this first-hand via our social media pages and what kind of posts attract most engagement.” This appears to be confirmed by the popularity of KJ’s recent publication of Small Buildings of Kyoto, a photobook drawn from our popular Instagram series of the same name [see above]. (Another celebration of our 30th anniversary, in addition to the retrospective photo-show held as part of this year’s Kyotographie event in May).

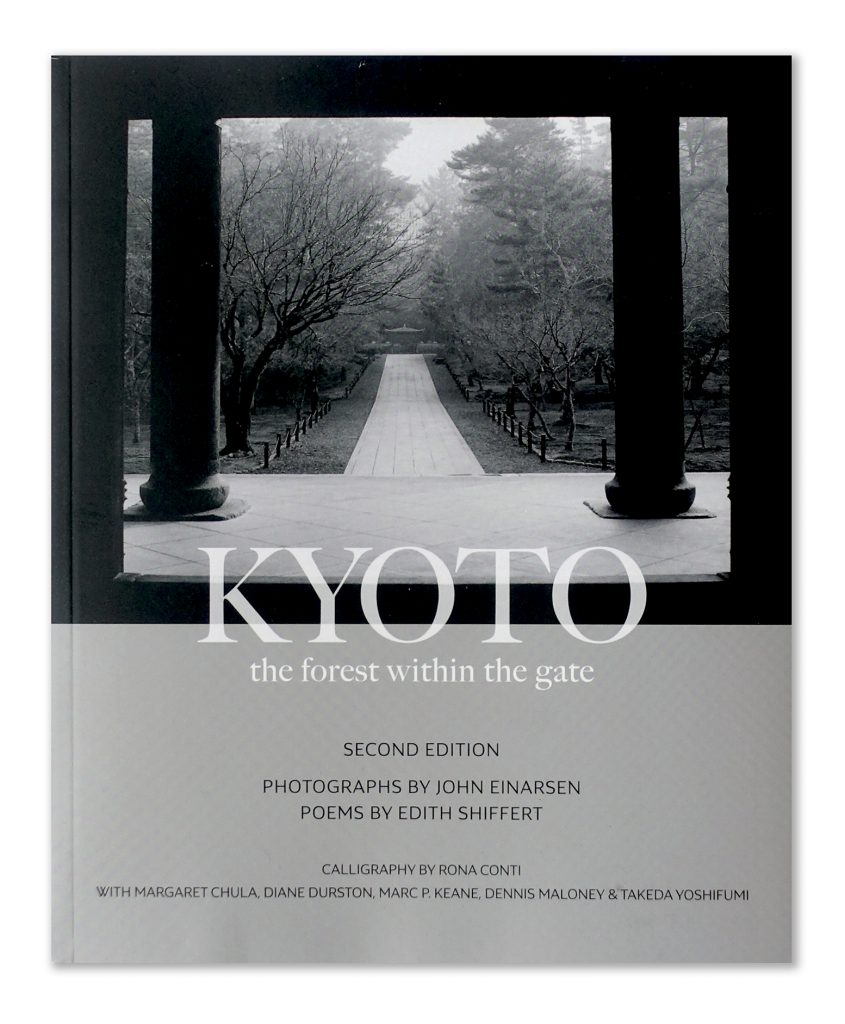

This project, KJ’s third successful crowdfunding campaign, reached its target, $10,000, in just 8 days, and went on to achieve 171% funding, allowing us to print 750 copies of SBK. In addition, as a tribute to Kyoto poet Edith Shiffert, who passed away this year at the age of 101, we were able to fund 500 copies of a new edition of The Forest Within the Gate, featuring Edith’s poetry together with John Einarsen’s photography, with a new essay by Margaret Chula and an additional poem by Dennis Mahoney, Edith’s literary executor (in addition to writings by Marc P. Keane, Diane Durston, and Takeda Yoshifumi).

This Indiegogo campaign was boosted by an exceptional array of perks organized by Lucinda: from postcards to bonus back issues of KJ to a tea bundle, Butohkan tickets, a special print offer, Kyotographie passports, ceramics, saké, exclusive watercolour originals, a two-day Walk Japan tour, a Gion Night Photography tour …and more.

All promised perks, over 300 in total, were delivered, including 40 copies of a special edition of SBK incorporating hand-made linocut prints by our talented designer, Hirisha Mehta, with a cover printed on the Shubisha & Hokuto letterpress in Kyoto and hand-bound by Muramatsu Kana. Crowdfunding demands intensive effort—in setting up, promotion, and follow-up—but done properly, it provides a very effective means of ensuring that a publishing project can be realized.

Next project—at around the time of publication of KJ 89—a KJ exhibition at the Okazaki Tsutaya, October 20th to Nov 10th. Meanwhile, Asia-related submissions to KJ are always welcome, for magazine, website or future website guest blog (a new, more active version of the website is slowly taking shape on the KJ horizon).

————————————————–

Thinking about the interplay between innovation and convention in the ongoing history of how we read, I am reminded of Jorge Luis Borges’ essay, ‘On the Cult of Books’ (in Other Inquisitions). In it, he references St. Augustine’s unease at seeing his mentor, St. Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, sitting at a desk and reading “without uttering a word or moving his tongue,” in the late 4th century, as described in Book Six of The Confessions. Borges identifies that unsettling transition to unvoiced reading as integral in the progression of the book towards being not a means to an end, but an end in itself. The remainder of the essay explores further developments in the devotional tradition of literary philosophy, in which the entire natural world came to be visualized as text in progress, to be read as universal truth.

Borges himself is well-known for envisaging the inexhaustible ‘Book of Sand,’ and the infinite ‘Library of Babel,’ the contents of which represents every possible combination of letters and punctuation that has ever been—or will be—written. Both, it may be inferred, are metaphorical representations of the universe, or of writers’ attempts to define it. Who knows what Borges would have made of the Internet, that infinite garden of forking paths seen so fleetingly through the screens we peruse so earnestly today?

The Library of Babel now exists—at least online—at https://libraryofbabel.info/, created by a dedicated Borges fan, Jonathan Basile. At present he says it contains all possible pages of variations on 3,200 characters—for mathematicians that works out at a total of 10 to the power of 4677. Finding coherence in this ultimate data-dump is another thing entirely. “After searching through endless books,” Basile says, “both in the process of testing the site and because I myself cannot shake the compulsion it produces, the longest legible title I have found is ‘Dog’.”

Coincidentally, longterm regular KJ contributor Robert Brady, author of The Big Elsewhere, has a new book ready to self-publish—in print, of course. Its title?

Build Your Own Dog.