The Writers in Kyoto commemoration of WW1 was timed to coincide with the centenary of the beginning of the Battle of the Somme on July 1, 1916. The event proved hugely entertaining and a worthy way to remember the nightmare undergone 100 years ago. There were recitals, family reminiscences, articles and letters from the period. We tried to be as inclusive as possible, with various angles such as Japanese nurses sent to help with the casualties, an Irish song, the African-American involvement, the female angle, the Canadians and a mention at least for the Australian Aborigines who took part in the war. A huge thanks to Felicity Greenland for adding to the occasion by putting together a couple of splendid medleys of war songs and for leading the singing in such fine manner (and an homily to preserving the records of ordinary folks as a way to never forget). Finally, many thanks to Eric Johnston whose idea the whole thing was and without whom it would never have taken place.

Here’s the programme:

Ist session:

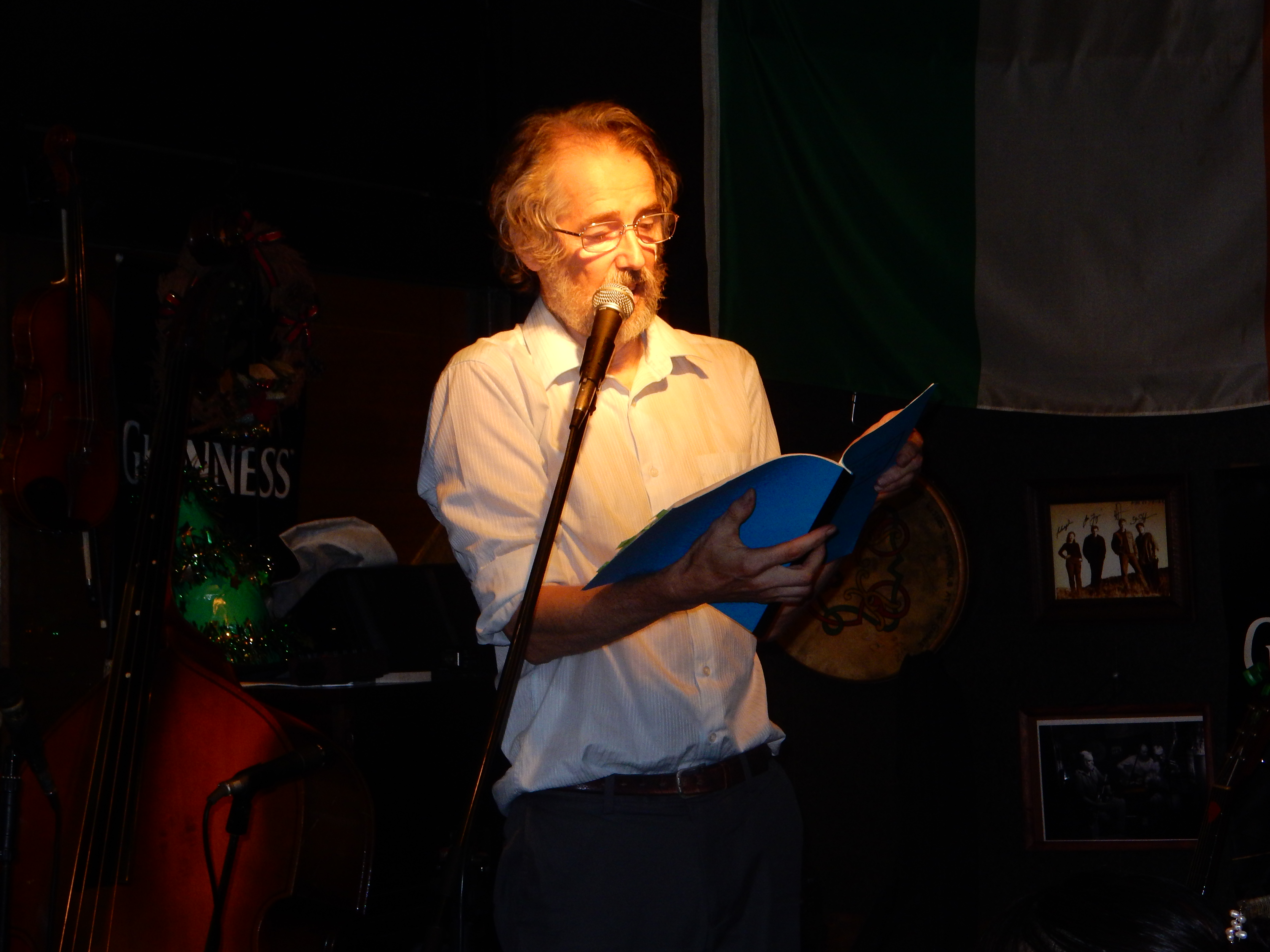

John D. (brief introduction)

Lawrence Barrow (Wilfred Owen)

Mark Richardson (Thomas Hardy)

Araki sensei and Paul Carty (Japanese nurses)

Ken Rodgers (maternal grandfather’s personal account)

Preston Houser (Frank Scott, Villanelle)

Felicity Greenland: singalong medley of WW1 songs

2nd session: 8.30-9.00

Felicity Greenland (song: Willie MacBride)

Gordon Maclaren (John McCrae/Canadian involvement)

Bridget Scott (Vera Brittain)

Preston Houser: (Dylan Thomas)

Kev Ramsden (African-American involvement)

Eric Johnston (US politician/Brit journalist)

John D. (Siegfried Sassoon)

Felicity Greenland: singalong medley of WW1 songs

Here’s the opening address (by John Dougill):

On this day 100 years ago, the Battle of the Somme broke out with a massive bombardment by Allied Forces against the enemy, who dug in and largely survived. As a result some 20,000 Allied troops were mown down in their ‘over the top’ attack on the opening day alone. The battle lasted nearly five months, by which time the Allies had advanced just five miles. Those five miles of mud and blood-splattered fields cost half a million deaths on both sides – one million in all. The battle has since become a symbol of the horrors of warfare, and in particular trench warfare abetted by the products of civilisation – machine guns, tanks and chemical weapons. ‘Lions led by donkeys’ is the phrase often used to describe the mix of frontline bravery in contrast to the ineptitude of generals, politicians and clergymen who urged them on from the backlines.

Lest we forget, the Allies in the war were Gt Britain, France, Russia, Italy and Japan, with the USA joining from late 1917. Against them were ranged the Central Powers, consisting of Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire.

The Somme was simply one battle in a war that had begun in late June 1914, when Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated by a Serbian nationalist in Bosnia. Four years later, 9 million soldiers had been killed along with 21 million wounded and a further 10 million civilian casualties. The scale and statistics are mind-numbing. Germany and France for instance sent 80% of young males aged between 15 and 49 to the battlefield – 80%. The eagerness with which the war was embraced by patriotic youth is another striking phenomenon, with many lying about their age in order to volunteer. The youngest authenticated casualty was a lad from Lancashire who was aged just 12.

We’re gathered here tonight to commemorate those who died, to honour their sacrifice, to never forget, and to give gratitude that our generation has never had to face anything of that kind. Most of all, as writers we’d like to show our appreciation of the remarkable poetry and other inspirational writings that came out of that great nightmare we call WW1. And in that spirit, I’d like to call on Lawrence Barrow to recite to us poems by one of the greatest of all the war poets, Wilfred Owen….

DULCE ET DECORUM EST

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime . . .

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent(14) for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Wilfred Owen

Thought to have been written between 8 October 1917 and March, 1918