(560 pages)

Readers of this website may remember that I wrote a piece called “Insight on a Rainy Day” in August 2022, largely about the Heart Sutra (Hannya Shingyo) and its central message, “Emptiness is none other than form; form is none other than emptiness”. It was a surprising serendipity then, to hear Ruth Ozeki herself, in an interview to Guardian Live about her most recent (fourth) novel, The Book of Form and Emptiness, saying that the title came from that very phrase. She is a Zen priest and familiar with the Heart Sutra. I wrote to her via her website and asked her permission to write a review for Writers in Kyoto, and she assented, mentioning that she herself used to be a Writer in Kyoto back in the day and is very nostalgic for Kyoto. In the interview she said that her personal view is that “emptiness” (ku 空) is like an ocean, from which waves or “form” (shiki 色) appear for a time. They are what we know as “matter” or the “material world”, and include inanimate objects as well as human beings. We all, we members of the material world, have form for a time and then sink back into the ocean.

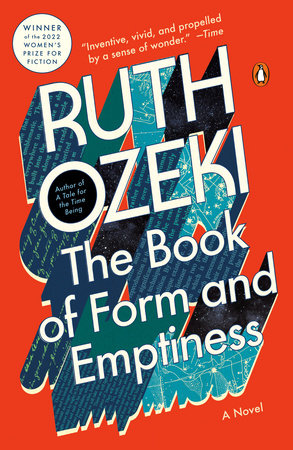

Ruth Ozeki is an American-Canadian author and Zen priest, born in 1956. Her mother was Japanese, but the name Ozeki is a pseudonym. She has written four novels in which environmental, spiritual, and social themes combine. She has received the Women’s Prize for Fiction with her latest book, and previously was awarded the Booker Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction.

She graciously gave me some details of her time in Japan. She lived in Kyoto 1976-1978 and 1980-1986, She did not study Zen at any Kyoto temple, but was more interested in the Zen arts, including Noh theatre and ikebana. She ran an English school called The Speakeasy near Ginkakuji, which emphasized language learning through theater and movement. She studied as a foreign student at Doshisha and Nara Joshidaigaku, and taught at Sangyo Daigaku. At the time she was trying to write fiction, but “didn’t really have the technical skills yet”.

********************

The Book of Form and Emptiness, Ruth Ozeki’s fourth novel, which apparently took eight years to write, centers around a teenage boy who, after the untimely death of his father, begins to hear voices emanating from inanimate objects. This is the dime version of the plot, which is actually much more complicated. The novel seems to be set in a US northwest coastal city. The boy’s parents, Kenji (a Japanese jazz clarinet player) and Annabel (a would-be librarian, handwork enthusiast, and press cutter) are rudely separated when Kenji meets with a fatal accident and, soon after, Annabel finds her job put in danger by the rapid decrease in print media. Annabel painstakingly saves the original materials of articles she is paid to collect, and also craft materials that she hopes to make into things; she becomes a hoarder, in the way of such people – the things she collects attain a critical mass and she can no longer handle them. She falls deeper into a depression as, now a single mother, she must handle her grief at losing her husband and also the disturbing mental state of her son.

After his father’s passing, Benny begins to hear the voices of objects. After one incident at school, he is evaluated, medicated, and sent to a children’s psychiatric ward for a time. Upon being released and having to resume his life, he finds a quiet retreat – an isolated corner of the public library, where he has some unexpected encounters.

The novel is set up in a rather complicated way, since the book itself becomes one of the characters with its own voice. The various fonts used give some clue as to who is talking at any given moment, especially Benny’s conversation with his own story as told in the book. By encounters in the library, especially the defunct bindery department in the basement, he realizes that books themselves, whether blank or written, are a kind of “emptiness” or potential. In the interview for Guardian Live, the author said that “books only come to life when they are read”. In that sense they are both the completed thoughts of the author and the potential to become something else, or to add to the original idea, in the mind of the reader.

She is sensitive to the way objects can tell their own story. They have lives (and deaths), they have things to say. There is elegance in the parallel between the main character Benny’s sudden ability to hear the voice of objects, and the many objects that clutter the space of his house and also the mind of his mother. In another thread of the book, Benny is diagnosed (by a sincere but very young and inexperienced psychiatrist) and put into a situation where he is unable to articulate what is happening to him, or to be listened to when he tries. The only people who accept that his new ability to hear the voices of objects may not be a mental illness, but a new and poetic way of hearing the world, are “outcasts” from society themselves. (Everyone has, no doubt, wanted to step outside the rooms of stultifying society and breathe the free air of one’s own truth. Encounters with these characters give the reader a sense of vicariously experiencing this freedom.)

As a writer, Ruth Ozeki said she doesn’t make outlines of the plot or the development of characters. (I can relate to this, as in my fictional short stories, I imagined the characters and then just stepped back to see what they would do.) She has a biracial upbringing, and this has enabled her to have different perspectives and see different sides of reality. She became interested in Zen as a young girl when she would come upon her grandfather sitting in meditation, and learned to do it. She realized through a stormy adolescence that this kind of spiritual discipline was a good tool for life, and was ordained as a Zen priest in 2010. This latest book, and the previous one, A Tale for the Time Being, particularly, have many references to Zen ideas and practice.

When I heard that this book had been published (it appeared on the WiK website) I immediately ordered it, as I had read her other novels and enjoyed them. At that time it was available only as a hardback on Amazon (I don’t use e-books). I ordered it as a hardback though I don’t usually do this, and I was glad I did, because this is a substantial book, with its own consciousness and presence, and I often stroked its covers as I was reading. I even took off the dust jacket – the book itself is a lovely sky-blue color – because its “naked” self evoked memories of libraries that have changed my own life. So much of the book takes place in a library. Ruth Ozeki herself appears there, as an observer in her own story.

*************

To learn more about Ruth Ozeki and her writing visit her website here.

For more book reviews from WIK click here.