In September 1995, I traveled to India to commence my sophomore year in an alternative Quaker program with eight international centers and experiential learning at its core. After two months of Area Studies at our center in the southern technological hub of Bangalore*, I headed for Kathmandu to participate in a 10-day silent Vipassana meditation retreat at the foothills of the Himalayas, and then flew back to India with a desire to assist Mother Teresa and her Missionaries of Charity in serving the “poorest of the poor”. My time in Calcutta* would be one of my strongest initial connections to Japan, although there had been subtle callings throughout my life – the embroidered figure of a geisha designed by my grandmother and framed on her wall, the silent discovery of Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes at my elementary school library at the age of eight, and an encounter with a Japanese high school student through my mother’s work with a locally-based international exchange organization.

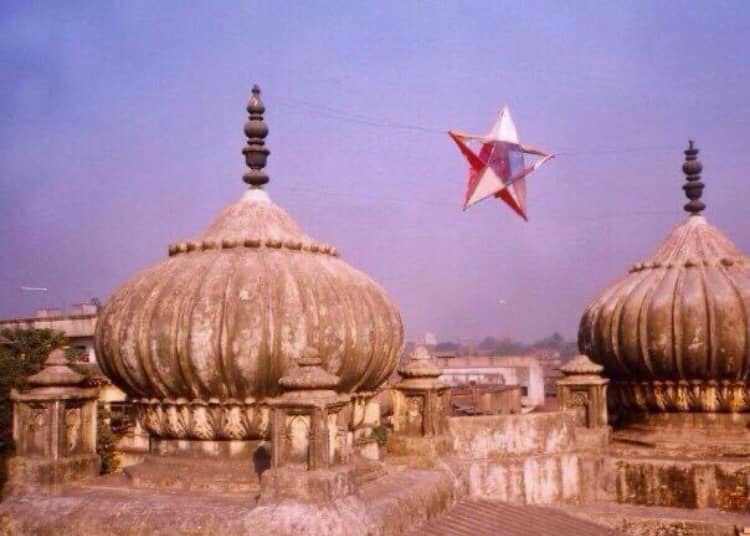

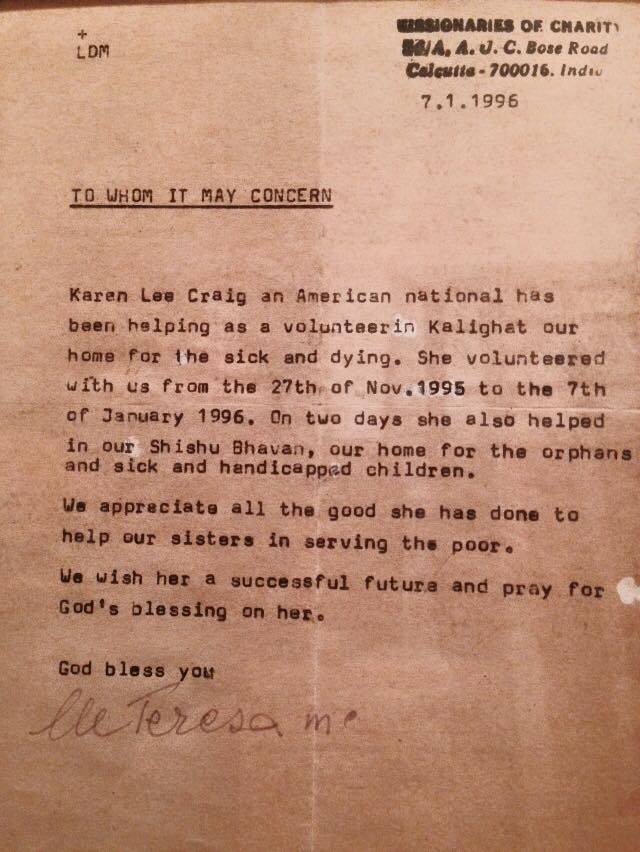

A sari-clad sister at the Mother House helped me to choose Nirmal Hriday (“Home of the Pure Heart”, formerly “Mother Teresa’s Home for the Dying Destitutes”) as my main work site, and registered me into the system with a small, manual typewriter. Nicknamed by the volunteers for its location, “Kalighat” was minutes on foot from the Calcutta Metro. One of the first volunteers I encountered was Joji, a man from Hokkaido (Japan’s northernmost island), who had a wide smile and reassuring, warm energy. The language barrier between us was largely insurmountable, but he soon introduced me to his girlfriend Naomi from Fukuoka Prefecture in the south, my future husband Toshi from Kanagawa Prefecture in the east, and several other Japanese volunteers who were close-knit, but accepted me into their circle immediately.

While working we were all intensely focused; there was always something to be done, and time was fluid. In accordance with our gender, we moved freely through the men’s and women’s sections to hold hands, massage limbs, bring food and tin tumblers of water to open mouths, and I’m not sure if others did this, but I often liked to sing songs to those I was sitting with. Residents were brought to the back of each room to receive a shower, and the dishes and laundry were washed in an adjacent room. Inevitably, we also tended to those on the verge of death (who were moved to a designated line of beds at the front), as well as those who had just passed. Toshi was viewed by the sisters and Indian volunteers as a dedicated worker who would happily take on any task, and therefore was called on two or three times daily to lift the deceased onto stretchers and carry them several minutes through the busy streets, to be cremated at the ghats on the bank of a waterway which flows to the Hooghly River. During midday breaks, the volunteers of many nationalities and faiths gathered on the spacious roof terrace to enjoy a treat of large, cakey German biscuits with strawberry jam. We then slipped into our checked work aprons once again.

Calcutta has been called the City of Joy, and perhaps so because of the strong spirit of its people. The volunteers, similarly, moved through their days with an inner rhythm and resilience. Kalighat’s residents always seemed happy to see us upon our arrival in the morning, and those whose illnesses were not severe would often raise their arms and call us over to their beds. I did not have a working knowledge of Bengali but came to understand some essential terms (food (khaabaar), water (jol), etc.), and the sisters would often act as interpreters if they were standing nearby. When there were no words, tenderness was a smile and service in action – doing, as Mother Teresa said, the things that no one else has time for. Observing my Japanese friends who had arrived in Calcutta before me, I developed a growing understanding of the Japanese national character. They not only remained in high spirits, but were kind, caring, sharing, excellent listeners, and the best friends I could have had while carrying out such emotionally challenging work.

We spent our leisure time gathering in hotel rooms not much larger than a single bed, chatting over Tibetan momo, puffed puri and disposable earthen cups of ultra-sweet chai at street stalls, sticky sweet gulab jamun and jalebi, and a mango, sweet or salted lassi at the Blue Sky Café, a backpacker favorite which is still in business on Sudder Street. One day Joji, Naomi, Toshi and I sat side by side in the back seats of a large arena, taking turns dipping into various colorful bags of Indian snacks we had brought to share. We simply desired ample space and mild air conditioning – a relief from the glaring sun and bustling pavement. We paid little attention to the circus on stage until the wild cats’ tricks were suddenly interrupted by a gushing shot of tiger urine through the bars and into the audience. Those in the front row shrieked but were prepared; they quickly covered themselves with a large plastic tarp.

Perhaps I became too daring with the food I put into my belly. The longer we spent in the city, the more willing all of us were to eat as the locals do – forgetting to ask for “no ice” in our drink glasses and unable to resist the pull of the deliciously-smelling cuisine of the street vendors. My hotel window, overlooking Kyd Street, had one large wooden shutter plank which opened outward, letting into the room what I considered a euphony of sounds, enveloping me in my chosen home away from home – pedestrians’ chatter and the singsong of vendors’ cries, autorickshaw motors and bulbous rubber horns, the rhythmic clip of a manual rickshaw puller accompanied by the sound of large, wobbly wooden wheels and a tin bell carried in hand by a short, thick rope, and the squawking of large birds, some of which would perch on my windowsill. I could no longer keep food down in my final Calcutta days, and from this large window I could see Toshi at the manual water pump on the street, rinsing buckets before climbing two flights of winding stairs back to my room.

When the day arrived to return to my school in the south, Toshi hopped onto the train and traveled three days, ticketless, to assure my safety. He hadn’t had any time to alert his friends that he was leaving Calcutta, but Joji and Naomi had dutifully packed all his belongings neatly into a suitcase and brought it into their already cramped room, ready for him if he returned (which, of course, he did).

Just days prior to arriving in Calcutta, the instructors of my Vipassana meditation retreat in Kathmandu had provided guidance on how to transform our bodies into vessels of loving kindness, boldly radiating streams of positive energy throughout the darkened hall and the city, across Nepal and the entirety of Asia, and finally across the world. The sisters and the volunteers I met in Calcutta provided a model of loving kindness through direct action. And the work ethic and goodness of my Japanese friends convinced me that I had to venture to their country eventually, to live amongst such people and to analyze what made them tick. It was what I had been searching for all along.

Toshi’s face was one of the first I encountered on my very first night in Japan, in July 1999. Instead of sharing an Indian meal with our right hands, we meandered down Tokyo’s brightly lit back alleys and, as I messily slurped my first bowl of ramen, we reminisced about the challenging, yet rewarding days which served as an initial bridge between our cultures. Seven years later, Joji and Naomi would travel from Sapporo to Yokohama to be present as special guests at our wedding reception, at which my new father-in-law offered special words of gratitude to Mother Teresa and the city of Calcutta. Indeed, reverberations continue. It is perhaps because I still share life with one of my fellow “co-workers” that I still reflect on that short and profound period of time in my late teenage years, and consider one of Mother Teresa’s quotes, Do small things with great love, to be an enduring life motto.

*The names Bangalore and Calcutta were changed, respectively, to Bengaluru (in 2014) and Kolkata (in 2001), but in this essay I have kept the names as they were when I resided there.

More photographs of Nirmal Hriday can be found here.