—A rock has a hundred faces, the Japanese gardener said.

I thought of asking why not two-hundred, but this was one of Sawamura’s greatest hits, up there with Nature is always right, the latter spoken in his Kyoto-accented English.

—Sensei, I said, —all this nice weather and no jobs. What’s up?”

—Keeping a low profile.

I lifted an eyebrow.

—For a few more weeks. Safer that way, he said. —Besides, that last job paid well—— too well.

—The big boss’s place in Ashiya? I said.

Ashiya, the posh hillside neighborhood above Kobe, home to Osaka’s business elite. Think the Peak in HK, the Hollywood Hills, sunny Montagnola overlooking Lake Lugano (where Hesse wrote Siddhartha).

Sawamura nodded, stuck a Short Hope cigarette between his teeth and struck a kitchen match from the big red and yellow box on the table of the tiny jazz joint. He drew in, the tip glowing red. He exhaled a pea-soup of smoke.

—You remember when I asked you to go buy me more cigarettes and have a coffee with the change.

—Sort of. So?

—A stone has a thousand faces, he said.

I nodded, ignoring the ten-fold proliferation.

—You need to read the rock, find which face is right, he said. —Then you bury ninety percent of the rock.

Why, I wondered, would you bury nine tenths of a boulder that cost more than a BMW.

—It’s what we always do, he said. —So the right face pops and the others don’t intrude.

—Right. I nodded, awed at the aesthetics-über-alles audacity, embarrassed that I’d never noticed, … suspecting that ninety percent was a figure of speech.

—Well, our client didn’t realize how much digging we’d be doing.

—He was clear about the location, I said.

—Yeah, very specific. Too specific. Something about Granny wanting it there. Not the placement I had in mind. But who’s to argue? Not with the big boss.

—So?

—So, if I had bothered to wonder why … Never mind. So during our usual after-lunch nap I took a shovel to check the ground. See what was under the topsoil. Whether we’d need heavy equipment.

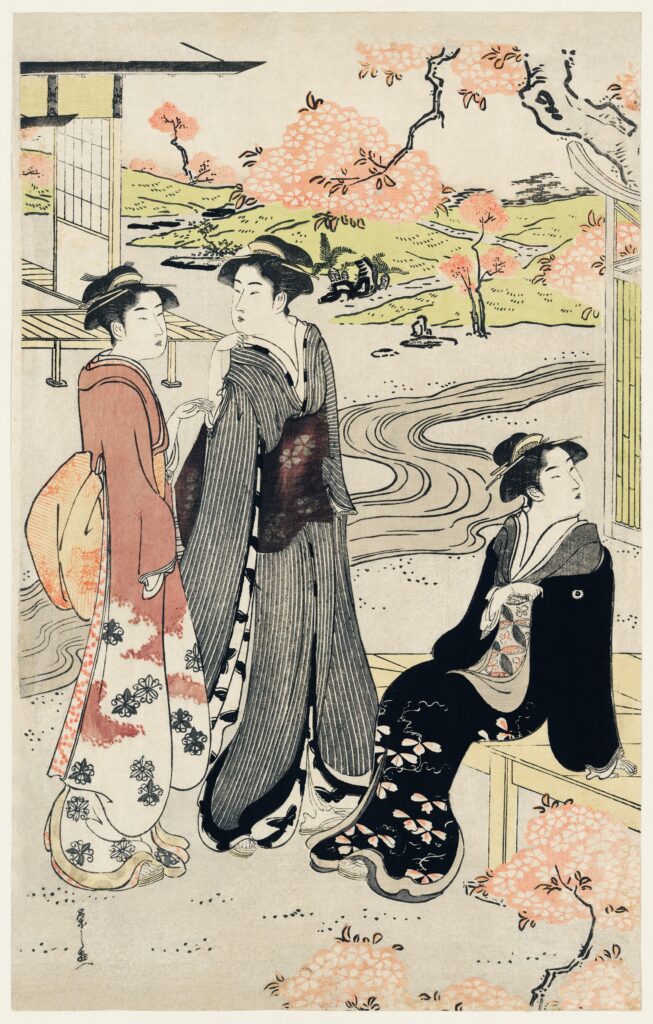

—Obaasan, Granny, the boss’ mother, was watching me, holding her bamboo pipe, lighting a bowl now and then. Kneeling, butt-to-heels, on the engawa, the wraparound veranda.

Sawamura gave me a long stare. —This is where things get strange, he said.

—I start digging and I hear this sharp crack, like maybe she dropped the pipe.

—I turn around, real casual, like I hadn’t noticed. Obaasan is holding her pipe upside down and backwards, pointing the stem at me.

Sawamura clamped his cigarette between his teeth, opened, then closed his right fist, forefinger pointing at me. I watched as his finger curled back on itself. A shiver hit the base of my skull.

—I bow, Sawamura said, —to apologize——for what I don’t know. Granny doesn’t take her eyes off me, so I bow again, deeper, holding it. Out to the side I glimpse the boss. I look up. The boss thrusts his hands into his pockets and steps out, eyes narrowed, cool, like a cat creeping up on a pigeon, smelling blood. You don’t ever want to see that. Civilians, they stagger backward, soil their knickers, buckle. Why the dread? You wish your time was up, but it isn’t, not yet. And the guy’s doing diddly-squat, just walking, hands in pockets, all the time in the world.

It was like I was viewing the scene in Cinemascope …

—Just in case, listen closely, Sawamura said. —Here’s what to do.

I ignored an urge to go to the little boys room.

Sawamura hardened his gaze. —Here’s what you do, he said again.

I nodded.

—You kowtow, and don’t say anything, don’t move a muscle. Forehead to the ground, kowtow.

I nodded again.

—The boss. I can’t see him but he’s standing over me. ‘Sensei,’ he says. The boss called me sensei. ‘Did I tell you to dig?’ I stay still, dead still. ‘I told you to set the rock here,’ he says. I hold my pose. Then, his voice calmer, ‘Why are you digging?’ he asks. Without lifting my head, I say, ‘A rock has ten-thousand faces. Only one is the right face.’ I wait for that to sink in. Then, ‘The other faces must be buried to quench their jealousy, to ward off evil spirits.’

This was a new twist.

—The boss hunkers down, lifts my chin with what’s left of his pinky. The ink starts at his wrist and keeps going.

Reflexively, I checked Sawamura’s fingers. All digits accounted for.

—Then he says, ‘Okay, sensei, do what I say. Bring in the power shovel and get your long-haired gaijin yarou out of here long enough to finish the tricky part. Tell your crew to keep napping.’

Being called a foreign a-hole was par for the course.

—He’s this close to my ear, Sawamura said, spreading his thumb and forefinger.

—His stump’s raising my head so I have to look Granny in the eye. ‘Of course,’ I say through my teeth. He drops my chin.

Rumor had it she was the real power behind the underworld throne, at least until her hated daughter-in-law edged her out. Only a toothless Obaasan could stomach the atrocities ascribed to her, they said, circular logic and misogyny be damned.

One that lodged in memory was the Osaka ramen cart’s noodle broth made with human hands. Stewed from human hands. Cooking, clearly a woman’s idea, ipso facto Granny’s. Why hand soup? To erase fingerprints and, perhaps, to indicate the crime: tenuki, a sloppy job, literally “hands removed.”

Months later, a wrist-disarticulated corpse was found in a bamboo grove near Takarazuka, town of the eponymous century-old, all-female (see!) musical revue. The forensic pathologist said severance was by chuuka houchou, the wide-bladed Chinese cleaver used for chopping pig ribs and poultry into finger-length pieces you can eat by hand.

Sawamura was staring at me.

—How many? I asked, swallowing.

—Who’s counting? I dug it clean. Then I dug deeper. Pushed the parts down low and laid some soil on top. That was when you got back.

I remembered. Everyone joined in, pulling and pushing the boulder swinging from a chain hoist on a tripod.

Sawamura gave a tight smile and pulled out another Short Hope.

—Wakatta kai?

I copied his grimace, nodding. —Wakarimashita, I said. Got it.

—Homma kai na? Sawamura said. You sure?

—Hai, I said.

—Hey, he said, putting the cigarette between his teeth, —let’s live it up tonight. Go to a hostess bar.

No, I thought, not that B.S.

Sawamura could see I wasn’t enthusiastic. —Or a geisha party, he said.

I’d never been to one.

—And you can bring your foreign girlfriend, he said.

—I don’t think so, I said.

He lit the cigarette.

—What was that about evil spirits? I asked.

—You’d be surprised, he said, puffing on his Short Hope, —how the slim chance of avoiding death gets your creative juices flowing.

—Ten-thousand faces, I said, in a flat voice.

—I had to up the ante, raise the stakes, Sawamura said, —for him to listen.

—Nine-tenths of every rock? Really?

—What do you think? Sawamura said.

—So what’s to worry?

Sawamura looked at me like I was slow. —What if Obaasan is worried? he said.

Coda:

The porcelain-faced, crimson-lipped geiko, as geisha are called on their home turf, was filling my thimble of a sake cup for the umpteenth time. Up close, her hairdo was adorable, like a panda.

I turned to Sawamura. —Sensei, I said. —One thing I don’t understand.

He winced, exasperated. I was ignoring TPO, the ne plus ultra of Japanese etiquette: time, place, occasion.

—Isn’t it strange? I said. —Everywhere else, the wife brings out tea and snacks for our mid-morning and afternoon break. But at the big boss’s place … the whole time we’re there, I never saw her once.

—You weren’t sitting on the power shovel, he said.

My hand jerked, spilling sake on my lap. The geiko began daintily dabbing the wet spot with a hot oshibori.

Sawamura crowed at my come-uppance. —Now, he said, —will you shut up and enjoy the party?

###