Sophia is a witch so she ought to be able to think of a spell to make all the plastic sheets vanish.

To that end, two small and stylish frosted glass goblets, filled with apple juice and ice, are on the kitchen table. One goblet has a golden sun embossed on it, the other has a silver moon surrounded by three stars. The goblets were left by a previous tenant.

Impromptu spells are not Sophia’s strong point. “We’ll link arms and drink”, she suggests. Tatsumi, her husband, laughs, “That’s what the Viking warriors did”, he says.

“I’ll have the cup with the moon”, continues Sophia smoothly ignoring him, “you get the one with the sun.” She places the sun one in front of him, the moon one in front of her.

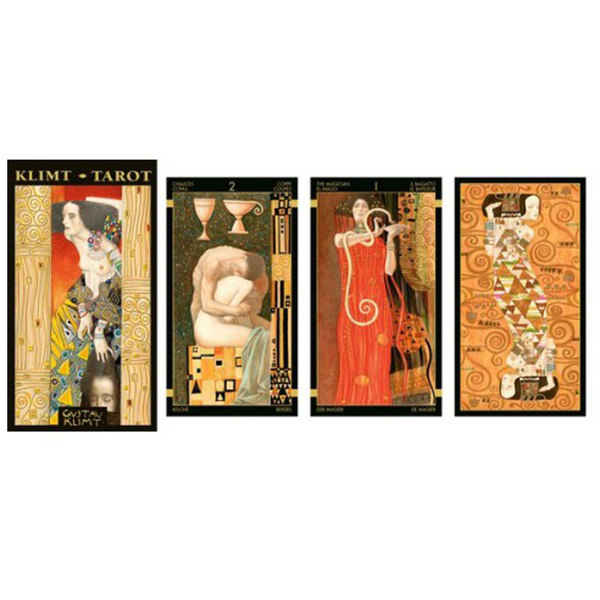

Then she lays out three tarot cards on the table: The Moon, The Sun, The Stars. The tarot deck is based on Gustav Klimt’s romantic and sensuous paintings. The Sun depicts a slim naked couple embracing erotically in a spangled fireworks of gold; on The Stars two dozing women wearing golden bracelets and muumuus are posed on the background of a silvery night sky; The Moon has a blond nude woman curled up asleep against a sea of dark blue, a sparkling crescent moon unfolds behind her.

Tatsumi’s face lights up with amusement. Sophia ignores him again. “I’m not going to do a reading, they are just here for atmosphere and to lend cosmic power.”

She waves her arms over the table, the cups, the tarot cards, and intones, improvising, “Good-bye, plastic sheet! Good-bye! The plastic sheets will depart from our land!”

Tatsumi starts laughing and offers a stinging critique, “It sounds like a spell made up by a little child”.

“Never mind”, she retorts, now giggling a bit. “Drink!” she commands, unable to keep a straight face. She picks up the glass with the moon and Tatsumi obediently picks up the one with the sun. She snakes her arm through his and utters a quick toast. “To no more plastic sheets! To no more plastic!”

Tatsumi obediently repeats her words and they take a gulp of apple juice.

“Peace, the charm’s wound up!” she adds, remembering one of her favorite lines from Macbeth.

Spell done, Tatsumi gets up and starts to boil some water for soba noodles.

Sophia gets some cold leftover oatmeal out of the refrigerator, sits back down, and drizzles honey onto the oatmeal.

“It will sound crazy, maybe”, she says, watching the translucent honey spiral down in swirls, “but sometimes I wonder if maybe I am a nature spirit traveling through this world incognito”, she says, “I don’t feel like I really belong here.”

“Hmmmm…well, which particular nature spirit do you think you are?” her husband asks in his trademark teasing tone. He turns around, holding a handful of dried buckwheat noodles, “a centaur? A tengu? A fairy? An elf?”

“Well, don’t laugh”, she said, “but I think I’m one of the nymphs of the Goddess Diana. That’s why when we moved to this neighborhood I found the yomogi growing next to the path near the mountain behind our house. And the deer on the same mountain. Deer are sacred to Diana. Yomogi is called mugwort in English, but its Latin name is Artemisia, named after the goddess of the moon. Because the underside of the leaf has a whitish cast, as though moonlight is shining on it. And you know, the first thing I ever ate in Japan was a yomogi daifuku.”

Climbing up a large stairwell in Shinjuku Station, after taking the train from Narita, that day 29 years ago, they had come across a man standing behind a table with rows of mochi rice cakes, some green and some white. Sophia had stopped and pointed at the green ones and Tatsumi had bought her one. Crushed yomogi leaves had been intriguingly blended into the mochi rice. Thus, her first impression of Japan had been an old fashioned one, the sort of thing she had never ever seen in the States: a vendor selling homemade simple food not wrapped in plastic, from a little table. Tatsumi had been amused at the way an ordinary traditional food of his homeland had charmed her utterly.

“That was a key moment. I think I was being tested. I just didn’t recognize it at the time.” She takes a sip of the magical apple juice then starts talking again, like the professor she is.

“Years later, I started interpreting literature from the standpoint of a witch and, please remember, that it is all the references to the goddess Diana in Shakespeare’s plays written which support my ideas that the plays hide the Divine Feminine. It’s like one of those computer adventure games I played as a kid: get key, pick up box. Don’t you see? You do it and later it’s clear why it all happened that way. It’s a message. It’s magic!”

Eat mugwort daifuku.

Get key.

Investigate the Bard.

Find Diana.

Become a witch.

Tatsumi has heard her theory how the yomogi daifuku in Shinjuku Station was some sort of message from the spirit world, but he realizes now Sophia is taking the whole far-out theory further by actually suggesting that she is working for the goddess Diana and now incarnated as an ordinary mortal, a humble scholar of Shakespeare. It had been a turning point in Sophia’s life when Macbeth revealed itself to her as a guide to magic and witchcraft.

Peace, the charm’s wound up.

“Well, of course, I have no proof, of course, except, well, I was born in July, under Cancer the crab―that’s the sign of the moon”, she says, stirring the golden yellow honey, one of her favorite things in the world, into the thick oatmeal with satisfaction.

Tatsumi is distracted by his noodles now boiling over. He turns down the heat, and the foaming bubbles sink peacefully. He is hoping Sophia that will similarly just calm down and forget all about her agitation, her unprovable theories, her airy nothing ideas.

Sophia, perhaps getting the hint, quietly sprinkles spices, cardamom, cinnamon, allspice on top of the oatmeal.

A comfortable and peaceful silence ensues. Tatsumi drains the noodles and chops some negi onions to put on top of the noodles. But as soon as he sits down to eat, Sophia starts talking again with more updates of witchy and supernatural news from her life.

“Another thing. Last week I went to that store near Yasaka Jinja on Shijo, I was thinking I ought to buy moonstones, if I really am to be a witch serving the goddess of the moon, but I just didn’t feel like they suited me and bought these amethyst earrings instead…”

Sophia tugs at the purple hexagonal stones dangling from her ears. Tatsumi politely looks up from his smartphone to glance at them.

“….But then, amazingly, just out of curiosity, when I got home I looked up the Greek myth of how amethysts were created. A young Greek woman named Amethyst was on her way to Diana’s temple and was chased by Dionysus who wanted her to go to one of his parties. Dionysus almost caught her but Diana changed her into a clear crystal. Then Dionysus caught up to her, and poured his purple wine on her, changing the crystals forever to purple. My favorite color, by the way. So no matter what I do, I seem to be surrounded by things related to Diana.”

Sophia gets up and puts organic cocoa powder in a cup, adds a little water and some soymilk and two large spoons of honey, “I know I’m obviously an ordinary mortal person. That’s clear. The question is if I’m also some sort of spirit. It would make sense. It would explain everything, actually.”

But Tatsumi, now scrolling through Yahoo news on his phone, is only half listening.

He wasn’t a bad person, not unkind, Sophia knew. He just wasn’t a radical activist witch like she was. He wanted peace and safety and stability. But she had to trust him and ask him to help her. She had no one else she could ask.

And she had so much to do. The worst, most awful, soul-crushing thing now was the huge heavy dark green plastic sheet covering a piece of land near a river three or four houses away from them. She wanted it gone.

No one but her husband could help her write and also sign letters in his name. Writing letters was one of her activist activities on behalf of the bugs, the birds, the animals. She didn’t just need his Japanese language writing skills: she was also afraid of being noticed by the government.

Japan was a lovely country, with many really kind people, but the government was basically run by the construction and chemical industries. It was radical collective capitalism. She didn’t think she’d be deported for speaking her mind but who could be sure? Some Americans who had staged demonstrations against the cruel dolphin hunts in Taiji had been deported.

The land near the river had started out as a large field, but the rapacious Japanese construction industry had turned that into twelve plastic houses and a long apartment complex, though there were empty and abandoned houses scattered everywhere in every neighborhood.

Building on green land was cheaper of course. The government provided free money to any construction company that wanted to build anywhere. Construction companies were the preferred route to stimulate economic activity.

Sophia had speculated on why that was. Why couldn’t the government send money to ordinary people to buy rice, clothes, land to grow food on, books?

Sophia guessed it was to do with power. The construction companies had a lot of political power, and they used a lot of heavy equipment, so they could promise that they’d spend the government’s money on new bulldozers, trucks, cranes, drills, concrete and such. The politicians were friends with all the people running the companies involved. It was a cozy world of favors, back-scratching, familiarity, paternalism and patriarchy. Factories, cars and machines were to be privileged above all else.

And the whole scene was also probably dictated by global financial markets beyond the shores of Japan. Sophia didn’t know the particulars, but she thought it was very likely that the people working on Wall Street and Washington and Europe and other financial and policy centers all over the world had their elegant fingers in this particular pie.

The toxic result was that all over Japan there were millions and millions of empty houses, shops and apartments. The country was immensely overbuilt. Green land was precious and beautiful, but the construction companies had all the power, so nothing ever changed and new houses were built on green places while millions of old houses were vacant. All the vacant houses and their land totalled a land area equal to the whole of the island of Kyushu.

And as for the little piece of land near her, after all the houses and apartments had been built on that little parcel of land, there had been one little odd strip of green land left, too small to be built on. Actually, it was quite big. It was maybe 300 meters long and 15 meters wide and it stretched down along the little river. You could hardly say it was a riverbank, because the river had steep artificial concrete sides, and the land was not sloping down naturally to meet the sides, but perched perpendicularly on top of the concrete, on the south bank of the river.

But with grasses and flowers, this narrow strip of land could have easily supported many, many ants, worms, grubs, grasshoppers, butterflies, crickets and be a home and larder for quite a few birds. It would be able to filter water, to cool the land, and to be a beautiful little piece of nature, spiritually encouraging to anyone who happened to see it. It was easily visible from the small bridge that spanned the river.

But it was covered with heavy green plastic, so it could do none of its magical natural functions. It was, for all purposes, a dead zone. Every time Sophia crossed the bridge, she had to avert her eyes from the plastic sheet zone. She felt so guilty, so upset, by this cruelty humans were perpetrating on nature just out of greed and laziness. She could hear the bugs and the worms moaning and screaming, buried under the thick green swathe of plastic. She could hear the plants shrieking, a mournful vibrating cry of many small voices, trying to seek the light and finding only heavy malignant plastic blocking the beautiful sun and the soft rain.

Sophia shuddered to think of the seeds carried on wind eddies and dropped from the sky onto the cold plastic, instead of soil. They all withered and died.

In truth, there were three or four other similar sheets of plastic, almost as large as this one, near their house and all of them troubled her and bothered her. One was on a slope reaching down to the drainage gutter next to the narrow asphalt path that circled the base of the small mountain near their house. One was on a strip of land next to a fence that enclosed land that belonged to the emperor. One was near another river. All of them were affronts to nature, symbols of human’s cruelty and lack of care for the other-than-human beings of the planet.

These creatures were already suffering major die-offs. Bugs had declined by 30% or 40% in some places in the country over the past few years, and it showed. Honeybees, ladybugs, butterflies, moths, praying mantises, and even mosquitoes, were rare now. Sparrows, common just seven or eight years ago, were no longer spotted hopping on pathways. The din of frogs that one used to hear during the rainy season was gone. The sound of cicadas was no longer a roar but just a little dim whirring sound. Nature was dying everywhere.

She felt this decline acutely and almost personally. Her sense of loss, injury and dread was almost personal. And it was this feeling of being wounded and suffering that made her think that logically, though she had no real proof, she might be a reincarnated nature spirit. Surely she could not truly be one of the humans.

Tatsumi had sent her letter complaining about the plastic sheet (which he’d translated into Japanese) to the City Office and received just a phone call from a city office bureaucrat explaining that it was now city policy to provide the sheets to prevent weeds.

She had tried bringing around a petition for neighbors to sign, and though people had been polite and generally signed it, it was clear that they didn’t care about the disappearing nature at all.

So she had given up, but she was still plotting, vaguely, against the plastic sheet.

She can’t say that she is a failure as a neighborhood activist. The truth is that she seems to be the only one who cares. For these sheets are popping up in all sorts of other places too: outside apartment buildings, on the perimeters of farmer’s fields.

She decides to make a cup of cocoa. While she is stirring the tiny black chia seeds into the cocoa, a totally irrational image pops into her head.

Black-clad figures covered from head to toe in material that swallows up their shapes race from one spot to another. They carry some small scissors and they cut the plastic away, freeing the soil, the plants, the tiny animals, the insects.

“I know what we can do”, she exclaims in excitement. Tatsumi looks up from his phone. “We’ll be like ninjas. We’ll dress in black and in the middle of the night, we’ll take the plastic away with scissors or shears”.

“But we’ve written a letter with your name on it, you’ve taken a petition around. The Shiyakusho people will guess who did it. It won’t be seen as a joke or as a light matter.”

She wants to cry. “Well, we can’t just give up!”

She feels the weight of all the innocent sweet natural beings who can’t have a home thanks to her inability to solve the problem and lift the tons of horrible plastic off of them.

Oh, when will the economy just go ahead and collapse so her agony can end? Then the stupid people who don’t care about nature won’t have any money for plastic. Then the plastic can’t be manufactured because the factories will all be shut down.

She knows objectively that is an antisocial thought, but at the same time, it’s not crazy at all. (That’s what is so crazy, really. This is the weird and schizophrenic era they are living in. Headlines scream “Collapse!” “Climate change disaster!” and “Apocalyptic forest fires!” but then people, including her, just go on about their ordinary lives, while sadly shaking their heads.)

“Look, Sophia”, Tatsumi says, “I agree with you about the awfulness of the plastic sheet. I do. I hate it as much as you do. But the people who want that sheet are in control of this situation and they have the power.”

She knows he is right. The plastic is all over Japan, behind apartment buildings, along the sides of roads. Like a successful monster which ate everything, and still eats it every day, slothfully reclining yet motionless as a lumpy carpet.

No one can stop it. It will go on just as long as it can and then it, too, will die, if a substance such as plastic can be said to die.

In her mind’s eye she sees, decades from now, a future landscape where the plastic is thin, ragged and tattered, the houses and apartments mostly empty. Then all empty.

Already many houses in her neighborhood are vacant. And there are more each year. Vines cling to the front doors, grasses sway in the small gardens that were so neatly tended just a few years ago. One house near her has a gigantic black mould spot, the thumb print of a greasy giant, on the outer wall on the second floor.

Another has, inexplicably, a heap of old broken gilt wooden picture frames and a battered plastic broom near its faded wooden front door.

For years, a frail but cheerful old woman with thinning permed and dyed red hair and a diligent yet absent-minded air, called out greetings to everyone passing by. Now her mailbox has a long strip of plastic tape covering its slot to prevent the delivery of junk mail. Her house stands empty, curtains permanently drawn.

Sophia has no idea if the woman died or if her relatives moved her into a nursing home. But somehow, that strip of fading green plastic on the mailbox she now realizes can surely be taken, along with everything else, as a sign from the gods.

******************

For more by Marianne Kimura, please see her story of Last Snow,; an account of how her second novel, The Hamlet Paradigm, was taken up by an independent publisher; her double life as academic and fiction writer; her third prize winning entry for the Writers in Kyoto Competition; an extract from a work in progress, Seven Forms of Infiltration; an interview with her about goddesses and ninjas; or an extract from her first novel, The Hamlet Paradigm. For her original story, Kaguya Himeko, please see here.