Tiny characters float within my vision as my fellow students are dedicatedly focused on writing the familiar to them but foreign to me. It is my first year of studying calligraphy. I love to watch Shimizu-san writing the most exquisite kana or onna-de (literally, woman’s hand), but know that I’ll never be able to emulate her elegant delicate work of haiku and poems. Nor will I write tiny characters on sheets of handmade paper like the focused Japanese students. I ask Kobayashi Sensei what they are writing. “Hannya Shingyo, she says. Complicated.” I look it up and find the Heart Sutra.

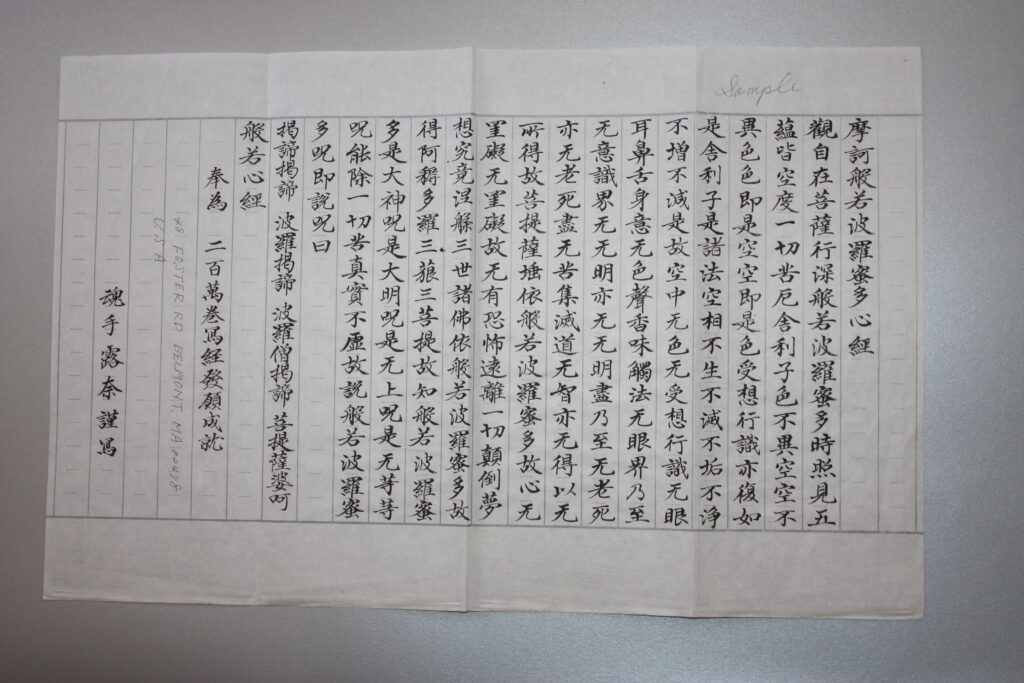

Sensei tells me that if I wish to learn to write the Heart Sutra, I must begin with large Kanji so that I can learn the characters, then gradually write smaller and smaller characters, like a pebble in a pond, but in reverse. There are 260 of them. I begin with her o-tehon (study sample) and find the work beyond challenging. There is tension in my hand. The characters are complex. If I make one mistake, I must begin again from the very first character. I will not know whether or not I have made a mistake until she corrects it.

Quite surprisingly, over time I am able to approach smaller and smaller versions. I realize that the smaller characters require the same amount of push and pull as the larger ones. One has to push down very gently, then harder to achieve a character of some distinction. The flow leads to characters not mechanical looking but with different thicknesses and tiny lines of connection. It is this push and pull with intricacy which must be present in order to have feeling and not tension show in the work. As it is said, “The Brush does not lie”.

The first time I write the entire Heart Sutra in its proper small size it takes me six hours. And all of this time I do not understand what I am writing. My legs fall asleep, no break until a full line is complete, I continue. I read in English what I am able to find about the meaning of what I am writing. Please know that this is in 2001. Alex Kerr has yet to write and publish The Heart Sutra.

A dear Japanese friend tells me that there is a temple where once a month devout Buddhists write the Heart Sutra, hear a lecture and finish with tea and sweets (my favorite). We go with my Sensei. Mihoko-san takes us early and introduces us to the Head Monk. I am embarrassed by my poor Japanese, but he is welcoming and smiling and says that he is very pleased to have a foreigner in his temple.

In the ornate room where the service takes place, we are given printed examples of three different sutras and paper upon which to write them. We bring our papers to our seats, and I am surprised that there are light boxes at each desk. Sensei is also surprised. She tells me that she has never gone to a temple to write the Heart Sutra. We both begin without tracing over the o-tehon as the other participants are doing. Far too soon a bell rings. Time is up. Everyone else has finished. Sensei is, of course, far ahead of me, but neither of us has come close to finishing.

Incense continues to fill the room as I listen to the prayers and see the son of the priest lead them. He is barefoot and moves with ease and precision. His body movements show the epitome of someone on the path to awakening. Then we all tuck our Heart Sutras beside the statue of Buddha with a donation. Afterwards we have tea and sweets.

The Head Priest disappears and returns with a book in English. It is about Soto Zen, the sect of Buddhism which the temple follows. It has a list of places in the United States where one can be a practitioner of Soto Zen. I keep the book as instructed. Two years later I return it with gratitude to the priest’s astonishment.

I continue to attend the once a month gathering at the temple. I am also invited by Sensei to join the monthly writing of the Heart Sutra in her studio. This is a surprise to me, both the invitation and the fact that the students do this once a month. The quiet, the incense, the concentration is all consuming, intense, and rewarding, except when Sensei checks our work. Each student worries about mistakes. Usually, I am the only person to have made one, yet I am enraptured with my studies and wish I had more time on my cultural visa. At the close of my studies I know that I must return at some point to Japan.

My friend, Mihoko-san, gives me a book with instructions for writing the Heart Sutra. At the back there is a list of temples where one can write it. They are in many places in Japan, some very distant. I am living in Gunma-machi, a very small town near Maebashi and Takasaki. Of the temples listed, some have regular monthly gatherings, others have made by appointment opportunities, and others require an introduction and recommendation by a Japanese in order to be permitted to write the sutra in the temple.

I plan my trip according to the temple calendars, ending with a visit to Koya-san, a place about which I have read with great anticipation. I bring my brush, sumi ink, paper for the Heart Sutra and a small suzuri inkstone, and, of course, a dictionary just in case it is needed. Though I have never studied the language formally, my Japanese has improved.

My first stop is easy, a large gathering of attendees who simultaneously work on the Heart Sutra. We pass our efforts together with a donation to the monk. I slip quietly out of the room so that I can explore the temple grounds.

Two more temple visits follow in much the same manner. Then, my next stop is one which requires an introduction and reservation. I arrive promptly and am ushered into a beautiful calming room with a Buddha altar and shoji (movable screens) which are open and give a view of an equally calming and exquisite garden. I am given not the Heart Sutra but rather a sutra written in that particular temple. I do my best but am unnerved when the Priest comes into the room to watch me, not once but repeatedly. When I have finished, he again comes into the room to tell me how pleased he is to see a foreigner making a special trip to write a sutra. I thank him and bow and know that it is my time to leave.

My next stop, the planned culmination, is Koya-san. I make a reservation to stay for three days at one of the subtemples. I am enthralled and surrounded by spirituality. Founded by Kukai in 816AD as the headquarters of the Shingon sect of Japanese Buddhism, it is the last stop or the very first on the 88 Temple Tour of Shikoku. It will be the first and last stop for me. (Years later I will walk a small portion of the 88 Temple Tour where often pilgrims are chanting The Heart Sutra.)

I have made arrangements to stay in a temple. The monks could not be more gracious, telling me that I am welcome to join the morning Fire Ceremony at 6 am. Surrounded by calm and meditation, warmth and the company of just a few participants, I feel honored to be allowed to observe and participate.

Feeling relaxed, I am ready to begin my mission. There is a university at Koya-san, where I expect to find the place for writing the Heart Sutra. I am guided to the room and rather shocked to see that it is a classroom. On some tables there are copies of the Heart Sutra which one can trace with a brush pen. There is no Buddha present, and the atmosphere reminds me of grade school with desks to match. I am incredibly disappointed. The room is deserted. No room to write with ink, I trace as homage and feel adrift. I find the bookstore where I buy a CD, ‘Chants of Koya-san’, with, of course, the Heart Sutra.

Upon returning to my lodgings, I am asked about my experience. I want to say, very politely and humbly, that there was no altar and no place to offer one’s effort to Buddha, nor enough space to set out my suzuri and other materials. I show the monk my ‘Four Treasures’; paper, brush, inkstick and ink stone. The paper is specially made to write out The Heart Sutra. I show the CD I bought. The monk is very gracious and surprised. Once again, I am ruing my poor Japanese. There is so much I wish to say. He intuits my disappointment. He says that I can write the Heart Sutra in a room reserved for large gatherings but with space to write in front of an altar. It is the perfect setting. I am alone in a huge room with the altar at one end and a ping-pong table at the other, perhaps alluding to my see-sawing emotions.

Each day I attend the Fire Ceremony in the morning, explore Koya-san, and write the Heart Sutra. Not knowing that there is a limit of three days for staying, I ask if I may stay for four more days. I am granted permission. I am enthralled with Koya-san, and there is so much to see

On the fifth day I am suddenly thunderstruck and self-critical. I realize that I have been given such a special opportunity, and I am egotistical and full of myself. Just because I write the Heart Sutra with brush and sumi ink instead of tracing with a brush pen gives me no more stature than others. If anything, I am lacking in spirituality. I am a foreigner and copying my Sensei’s guide. This realization does not take anything away from my sojourn, but it is a reminder that I am a student trying to learn and superiority is an incorrect path.

I have to return to Gunma-machi and, regrettably, end my year of calligraphy study. I am filled with emotion at the conclusion of my time in Japan. I am already thinking about how I will be able to return. My fellow students, at my Sayonara Party, present a fan with their farewell words. I have written a poem to Sensei, and my dearest friend Mihoko-san translates it. I read it at the farewell party. Sensei and I are both teary eyed.

My time to say goodbye has come. In the future I will live in Japan for extended periods of time to continue my studies. The Heart Sutra is more than calligraphy. It is a spiritual practice.