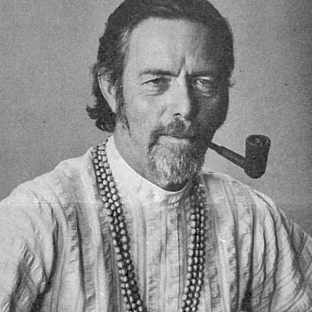

The following extracts are taken from pages 347-350 of In My Own Way, the autobiography of Alan Watts.

***************

Ogata-sensei arranged to get us into Ryoanji -– The Temple of the Dragon Hermitage – after visiting hours, so that we could see the rock-and-sand garden in the stillness before twilight, when all the tourist and swarms of schoolchildren had left. These gardens are strictly called ‘dry landscapes,’ and though everyone has seen photographs of this one at Ryoanji they give little idea of the place itself. It reduced us to immediate silence. The camera cannot grasp the whole scene, from the tops of the pines in the background to the whole long stone-edged rectangle of raked river sand with its nine island rocks arranged by miraculously controlled accident upon their beds of moss. One sees islands in a stretch of ocean, or perhaps just rocks on a beach, and the rocks are so scattered as to suggest vast space in the sand. There is nothing for it but to sit on the long veranda and absorb. Yugen. ‘To wander on and on in a forest without thought of return; to watch wild geese seen, and hidden again, in the clouds; to gaze out at ships going hidden by distant islands.’

The garden must be seen in its total setting: the low, roofed, and damp-mottled wall along one side, with the pines above; the calm, horizontal temple buildings with their sliding screens; the luminous deep-green moss garden just around the corner; the incense, the birds, the far-off traffic, the quiet.

Less well-known, and little troubled by tourists, is a comparable garden at Nanzenji designed by Kobori Enshu, and another, marvelously designed but not quite so happily situated, in the Honzan at Daitokuji. Guidebooks and loquacious priests have invented all kinds of symbolic meanings (which may be entirely ignored) for these creations. Such considerations stand in the way of realizing that they are astonishing demonstrations of the power of emptiness, and even that is saying too much. Lao-tzu explained that the usefulness of a window is not so much in the frame as in the empty space which admits light to the house. But people of the West with their heavily overloaded ideas of God, will easily confuse the Buddhist and Taoist feeling for cosmic emptiness with nihilism – the hostile, sour-grapes attitude to the world implicit in the mechanist metaphysics of blind energy – which is hardly to be found in the Orient at all.

*************

Kyoto must contain thousands of tiny, tucked-away restaurants and bars in narrow streets and alleys, and also has long arcades of small shops selling colorful stacks of dried fish, huge radishes, persimmons, all types of seaweed – dried or pickled – octopuses, squid, sea bream, tuna, globefish, soybean curd, leeks, eggplant, and a multitude of vegetables, pickles, and pastes that I have not yet identified. I wish I had my own kitchen there, though I am happy to sample the restaurants, particularly the bar-type ones for sushi, tempura, and yakitori where the food is prepared right before you. … One such restaurant, which serves both sushi and yakitori, calls itself a dojo or gymnasium for saké drinking and here the cups are not only generous – as distinct from the usual minuscule one-sip cups – but the bottles mighty. Unlike the Americans, the Japanese have no sense of guilt whatsoever about drinking, and this goes for priests as well as laymen. I remember Kato-san telling me about his Zen teacher: ‘Today I had retter from my teacher. Ah so! My teacher he very drunk. Much, much saké. He rive in ronery tempuru high up in mountain. Onry way to keep warm.’

I do not, alas, speak much Japanese; only enough to direct taxis and order food in restaurants, helped out with Chinese characters in a scratchpad. Unfortunately the Japanese and the English find each other’s language is so difficult that we can only talk like children, giving a false if amusing impression of our mentalities.

I do wonder if this attitude to alcohol account for the fact that I have never seen anyone nasty-drunk, as distinct from happy-drunk, on saké, which is about as strong a drink as sherry. The Chinese drink far more fearsome liquors, mos of which taste like a mixture of paint remover and perfume (though I once had a dark brown substance as good as Benedictine), and seem to give alcohol an entirely innocent association with poetry and music (raku), which is written in the same way as happiness. Doubtless these people become alcoholics in the clinical sense, but I suspect that what we call a ‘problem drinker’ is as much a product of social context as of mere booze. Since to be drunk in Japan, and old China, is not considered a disgrace, no one drinks because he is miserable about drinking or in simple defiance of stuffily sober friends and relatives. The Japanese also observe the interesting and salutary social rule that nothing counts which is said in a bar.