A Personal Response

Though I have read a lot recently, I have written very little. I could blame any number of things, from the noise of my children to the gloom that doesn’t seem to disappear even when the clouds dissipate. Possibly I am lacking a sense of purpose in getting on my commute every morning for the nearly 16 years I have spent being an adult and being in Japan (basically those times overlap perfectly).

Reading has been my escape and my damnation of late. Picking up the news just emphasizes the things that hover over me, but picking up my books gives me chances to escape (without endangering my children anyhow).

However, even my escapes are interrupted, by the before mentioned children, and by my own thoughts, and so I have set up a schedule, where I will read for about 20 minutes, then clean or do something of obvious benefit and then come back to reading. I have found that I am not alone in having to limit the amount of time I am reading into these small chunks, as it has been brought up in many Goodreads comments and even in the recent Japan Times article on recommended books. (Japanese Books to Get You Through the Lockdown)

So, these self-obsessed ramblings were just to bring me to this point: It’s a hell of a good time to read short stories.

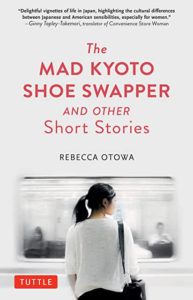

And so, my purpose, at least at this moment, is to tell you about a great book of short stories: Rebecca Otowa’s The Mad Kyoto Shoe Swapper.

Many readers will be familiar with the author’s previous published work, At Home in Japan, all about her centuries old family home near Kyoto. That book, while not short stories per se, was a collection of vignettes. Along with her new work, Otowa shows herself to have mastered the 20 page story.

So, what is the book about?

Story-wise, it could be said to be about anything and everything: ghosts, family, history, chocolate, Kyoto…

However, thematically it is obvious that the author has some larger ideas in mind and they pop up throughout, joining together the wide array of story subjects into a personal view of the world.

Possibly the largest theme here is the contemplation of what it means to grow older, with this theme stretched just a little more at times to look at what it means when you stop growing older.

Many of the short stories found here beautifully express the sadness and pain, as well as the wisdom and acceptance of becoming older. However, Otowa’s true skill is not simply in expressing these aspects, but in never forgetting that this point of view is not singular. The sympathy shown for the young characters, who often misunderstand or fight with elder ones, brings true power to the writing. Sympathy for older people doesn’t mean that youth is merely folly.

‘The Turtle Stone’ stretches across more than 60 years to show the rise and demise of a family’s sweet shop. The reader follows Taro from a young man trying to help with the business to an old man who can’t much remember the things he has learnt, let alone how to get home. However, the stages that Taro lives through appear to stretch beyond him to represent stages that we all go through, each one important, even if we tend to forget the ones we have stepped past. It is empathy, the old for the young, and the young for the old, that can bring us together.

This sympathy continues in what might be said to be the other major theme of this book, the possibilities inherent in women. As many of Otowa’s characters pass through the cycles of life, it is undeniable how these are different for females. The author presents completely realistic portrayals of times when the burden of duty weighs specifically heavy on the shoulders of females.

In ‘Gembei’s Curse’, Sachiko begins as the put-upon housewife domestically tortured by her father in-law, only to become the torturer of her own daughter in-law, Shinobu, as the cycle of life comes round. Will this just continue on forever? It will, unless something is able to stop it, like a simple apology: “Excuse me. I’m sorry I shouted at you. You do so much for me. I am grateful”.

This small apology results in putting a stop to generational abuse, but also to the abuse that women at times put on each other. One can imagine if the story were to continue it would lead to an even more understanding relationship when Shinobu grows old.

So, overall this is a work about age, the young and the old, and about the power of women and indeed all humanity unstrained by the bindings that are often thrust upon us. It is a thoughtful work, but not heavy and just perfect for someone looking for a quick escape.

To end I wanted to add a small quote that I found comforting in a time that has been uncomfortable. In the story ‘Rachel and Leah’, the former says in the midst of depression: “Gardens are forgiving places, there is always another chance next year.”

I found that a consoling idea, that up until this spinning, winding, ride of life is over, there is still a chance for something a bit better. Here’s to a beautiful garden, even if it takes a while to grow.