[A highly subjective and selective account…]

The first Europeans to set foot in Kyoto, in 1551, were the missionaries Francis Xavier and Juan Fernandez, seeking selfies with the Emperor Go-Nara, during the later throes of the Sengoku period of warring states. Not a good time in the old capital. Xavier described the devastated city as “a lair of wolves and foxes,” and after only 11 days, headed back to civilization: Hirado in Kyushu.

Kyoto was rebuilt, of course, and regained its attractiveness. In the late 1500s, another Jesuit, Luis Frois wrote about a Kyoto garden, describing its “delightful and strange trees … all of which were cultivated artificially, so that some are shaped like bells, others like towers, others like domes.”

By 1619, the political climate had changed again. William Adams’ associate Richard Cocks, of the British East India Company, recorded observing an execution of 55 Christians in Miyako (Kyoto). Soon, Kyoto was essentially a forbidden city.

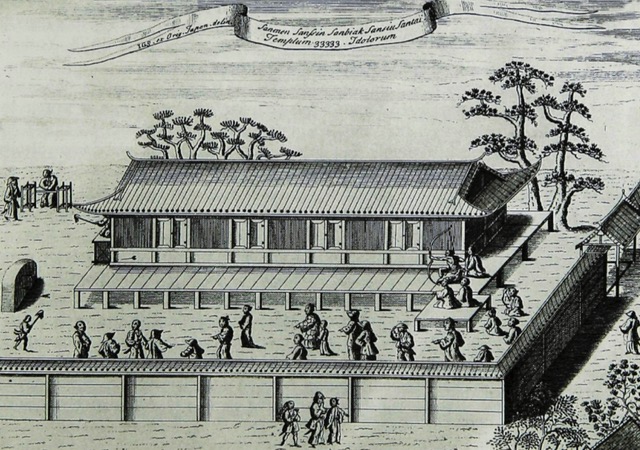

While the Tokugawa sakoku policy from the 1630s kept Kyoto almost entirely tourist-free for over 200 years, somehow the German naturalist & physician Englebert Kaempfer managed to snag an Airbnb close by Sanjo-keihan at the end of the 1600s. His writings on his two-year stay in Japan (published posthumously in 1727) became the authoritative text on all things Nihon for over 100 years, under the marvelously memorable title of “The History of Japan, giving an Account of the ancient and present State and

Government of that Empire; of Its Temples, Palaces, Castles and other

Buildings; of Its Metals, Minerals, Trees, Plants, Animals, Birds and Fishes;

of The Chronology and Succession of the Emperors, Ecclesiastical and Secular;

of The Original Descent, Religions, Customs, and Manufactures of the Natives,

and of their Trade and Commerce with the Dutch and Chinese. Together with a

Description of the Kingdom of Siam.”

Kobe and Osaka were not opened to foreigners until 1863, while Kyoto remained off limits for decades more. The indefatigable Victorian-era British travel-writer Isabella Bird visited Kyoto (with special authorization) in the late 1870s, and described the city’s delights as follows, in Vol. II of Unbeaten Tracks in Japan:

“With its schools, hospitals, lunatic asylum, prisons, dispensaries, alms-houses, fountains, public parks and gardens, exquisitely beautiful cemeteries, and streets of almost painful cleanliness, Kiyoto is the best-arranged and best-managed city in Japan.”

Lafcadio Hearn, here in 1895 for the Great Exposition (and the very first Jidai Matsuri), reported on it for the Atlantic Monthly, (a fascinating, glowing account now downloadable as A Trip to Kyoto):

“I returned by another way, through a quarter which I had never seen before, – all temples. A district of great spaces, – vast and beautiful and hushed as by enchantment. No dwellings or shops. Pale yellow walls only, sloping back from the roadway on both sides, like fortress walls, but coped with a coping or rooflet of blue tiles; and above these yellow sloping walls (pierced with elfish gates at long, long intervals), great soft hilly masses of foliage – cedar and pine and bamboo – with superbly curved roofs sweeping up through them. Each vista of those silent streets of temples, bathed in the gold of the autumn afternoon, gave me just such a thrill of pleasure as one feels on finding in some poem the perfect utterance of a thought one has tried for years in vain to express.”

Good point. Kyoto somehow speaks to everyone in their own language. As a more recent example, Gary Snyder, in the 1950s, found aspects of his beloved Pacific North-West here, in this poem from Riprap (1959):

Higashi Hongwanji

Shinshu temple

In a quiet dusty corner

on the north porch

Some farmers eating lunch on the steps,

Up high behind a beam: a small

carved wood panel

Of leaves, twisting tree trunk,

Ivy, and a sleek fine-haired Doe.

a six-point Buck in front

Head crooked back, watching her.

The great tile roof sweeps up

& floats a grey shale

Mountain over the town.

Here’s the same landmark, through the eyes of Edith Shiffert, in Kyoto Dwelling (1989). She came to Kyoto in 1963, and remained here until her death at the age of 101, in 2017. [See Charles Roche’s tribute to her at The Flame, here.]

Higashihonganji Pilgrims In winter sunshine hundreds of pilgrims come to bow at an altar then return to their countryside. Elderly, bent, short, in dark kimono and white tabi, they spread over the graveled yard. The all-pervading and ever-enduring compassion of Amida gives to them hope. Having left their work, going to go back for more work, gnarled hands clutch newly purchased rosaries, reach out to light candles and offer incense. The dream has at last come true, in the ancient capital paying homage at the supreme temple. The high and outspread eaves of the main building reach down toward them like mercy. Crowds of pigeons circle over them. Rainbow curtains at the gate, purple curtains on porches, blowing so they touch some of the faces.

Edith’s meditative verse is aptly complemented by John Einarsen’s photography in The Forest Within the Gate (2014). Harold Stewart’s By the Old Walls of Kyoto (1981) should also be remembered, as a measured response to all that Kyoto represents, while Gouverneur Mousher’s Kyoto, a Contemplative Guide (1964) probably remains one of the best introductory texts (from back in the day when Kyoto streetcar fares were 13 yen). John Dougill’s Kyoto: A Cultural History (2006) is another, more recent, classic distillation of this multi-layered city. Judith Clancy’s Exploring Kyoto: On Foot in the Ancient Capital (1997) is another must-read.

Many other writers have engaged with the mystique of Kyoto, all in their own distinctive ways. Pico Iyer’s local classic, The Lady and the Monk (1988) is half memoir, half romance. Recently posted on the WIK website, a 1957 poem by John Berryman grapples with the meaning of Ryoan-ji. Italo Calvino, the seer of Invisible Cities, also recounts a visit to Ryoan-ji, in Mr. Palomar (1983):

“…he sits on the steps, observes the rocks one by one, follows the undulations of the white sand, allows the undefinable harmony that links the elements of the picture gradually to pervade him.

Or, rather, he tries to imagine all these things as they would be felt by someone who could concentrate on looking at the Zen garden in solitude and silence. Because—we had forgotten to say—Mr. Palomar is crammed on the platform in the midst of hundreds of visitors, who jostle him on every side; camera lenses and movie cameras force their way past the elbows, knees, ears of the crowd, to frame the rocks and the sand from every angle, illuminated by natural light or by flashbulbs. Swarms of feet in wool socks step over him (shoes, as always in Japan, are left at the entrance); numerous offspring are thrust to the front row by pedagogical parents; clumps of uniformed students shove one another, eager only to conclude as quickly as possible this school outing to the famous monument; earnest visitors nodding their heads rhythmically check and make sure that everything written in the guidebook corresponds to reality and that everything seen in reality is also mentioned in the guide.”

In The Art of Setting Stones (2002), Marc Peter Keane shares insightful and very personal essays on the nature of Kyoto gardens. Other valuable additions include Juliet Winters Carpenter’s Seeing Kyoto (2012), Diane Durston’s Old Kyoto: A Guide to Traditional Shops, Restaurants and Inns (updated 2013), and Alex Kerr and Kathy Arlyn Sokol’s Another Kyoto (2016).

The eclectic Pan-Asian Kyoto Journal aims to remain a go-to source for diversely Kyoto-related articles. And in recent years the wide-ranging Writers in Kyoto annual anthologies have brought together a rich variety of prose and poetry, attesting to the ever-ongoing exploration of this fabled city’s confluence of rivers, traditions and minds…

**************

Links for pictures

Rakuchuu-rakugai-zu at Google Arts & Culture

Kaempfer illustration (PDF)