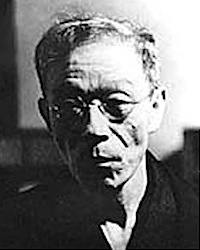

Although Kanazawa is recognized by UNESCO as a “City of Crafts and Traditional Arts,” it has also produced many great writers over the years, and, adding to this its impressive literary halls, museums, memorials, statues, celebrations, and even occasional author-themed foods, could well be considered a “City of Literature,” too. Izumi Kyoka is Kanazawa’s most celebrated writer – at least within Japan.

Kyoka was born in Kanazawa in 1873, only twenty years after Japan was forced to open to the West after 250 years of seclusion. As one might imagine, it was a time of great change throughout the country. Kyoka lived in Kanazawa until he was seventeen years old, and though he was forced to come back on a few occasions, his home thereafter became Tokyo – Japan’s literary center in his day and now – and for several years Zushi, on the Kanagawa coast, where he went with his wife, Ito Suzu, a former Kagurazaka geisha, to recover his health. Despite the short time he lived in Kanazawa, as well as the negative feelings he held toward the city, he set a number of his works there.

I became interested in Kyoka’s work due to a somewhat unique situation: he’s from the Japanese city where I moved to several years ago and expect to live the rest of my life. And although I read his stories before moving here, I was drawn to them more deeply after becoming a resident of Kanazawa.

It’s also of personal interest that some of his works are set in areas I might pass through every day. Visiting Renshoji, the temple on Mt. Utatsu where Kyoka set Rukinsho (“The Heartvine,” 1937), and the old castle moat where two characters from this story met while intending to drown themselves (as Kyoka and a local woman did in real life), is still possible today, though both places have changed in the years since he wrote it. Another of his Kanazawa stories is Kechou (“A Bird of a Different Feather,” 1897). This takes place near the Tenjin Bridge along the Asano River and on Mt. Utatsu, but at a time when those areas were populated by the “polluted” and disenfranchised: butchers, leatherworkers, prostitutes, grave diggers, corpse handlers, and other social outcastes. Because various temples, graveyards, winding streets, and even some houses still exist in those areas from that time, one can imagine what the river and mountain might have looked like when Kechou took place. Other Kyoka stories and novels also have Kanazawa as their settings, and whenever I come across them I feel my roots to the city grow deeper.

To me, the power and mystery of Kyoka’s stories are undeniable. While I admit having had only limited success reading his work in Japanese, Charles Shiro Inouye’s two collections of translated Kyoka stories are excellent, and what they transmit to me in my reading of them is of the same quality and effect as my favorite Japanese literature (also in translation): Kawabata’s Snow Country and Sound of the Mountain; Tanizaki’s The Makioka Sisters; Shiga’s A Dark Night’s Passing; Soseki’s Grass on the Wayside and Kokoro; Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion; Abe’s The Woman in the Dunes; Nakagami’s The Cape and Other Stories from the Japanese Ghetto; Ibuse’s Black Rain; Minakami’s Temple of Wild Geese and Bamboo Dolls of Echizen – among others. (Many of these authors knew Kyoka and revered him as a writer.) What differentiates Kyoka from all of these writers, his contemporaries as well as those who came after him, are both his pure Japanese-ness as a storyteller, which is to say the lack of influence in his writing from outside of Japan, particularly when western realism was in vogue, and also his writing style, which enabled him to develop an aesthetic that is arguably more surreal, more sensual, and more linguistically sophisticated than any other Japanese writer. His writing is often strange in the way that dreams are strange, yet his narratives are controlled, often intricately plotted, and expertly lead his readers through what typically are shadowy, otherworldly, deeply nostalgic emotional landscapes.

The characters and plot of my own novel, Kanazawa, present deliberate instances of intertextuality, where certain scenes I’ve written interact with certain scenes in Kyoka’s stories (and with his own life). Readers who have read Kyoka may recognize these instances, or at least trace some aspects of their lineage, in my novel. I could never hope to achieve what Kyoka did in his stories, stylistically or literarily; I’ve merely tried to weave something interesting together and add a layer to the ways my novel can be read, understood, and enjoyed. But one can still read Kanazawa without first reading Kyoka, I suppose one can also, if one wishes to, experience the same sense of recognition in reverse – by reading my novel first and then seeking out Kyoka’s works.

If readers enjoy my novel, or even only parts of it, and are curious to discover an important influence on its creation (and on my own life in Kanazawa), I want to point them to the following works.

Charles Shiro Inouye’s three publications on Kyoka are masterful. Two are collections of translated stories – equal to more famous literary translations by Edward Seidensticker* and Ivan Morris, but for some reason more quietly trumpeted than theirs – and one a critical biography. The former are In Light of Shadows (University of Hawaii Press, 2004) and Japanese Gothic Tales (University of Hawaii Press, 1996), the latter The Similitude of Blossoms (Harvard University Press, 1998).

Donald Keene’s chapter on Izumi Kyoka in Dawn to the West: Japanese Literature of the Modern Era (Columbia University Press, 1998) has long served as an excellent addition to what is available in English on Kyoka and his writing. There is general agreement that Keene’s work has been of particular importance to the revival of interest in Kyoka’s writing.

Cody Poulton’s Spirits of Another Sort is another excellent source of translation (plays, mostly, of which Kyoka wrote more than five dozen), and of critical and biographical material.

The more recent A Bird of a Different Feather, translated by Peter Bernard, beautifully illustrated by Nakagawa Gaku, and appended with several short but interesting essays by Japanese Kyoka scholars, is also worth readers’ time.

While other short publications deal with the creative products of what Akutagawa Ryunosuke referred to as “Kyoka’s World,” these are the ones I’ve read and come back to often with greatest pleasure and interest.

As Emmitt’s mother-in-law suggests in Kanazawa, if foreign readership of Kyoka’s work spreads, perhaps it will “help preserve something that’s in danger of disappearing.” I share her belief, and also hope that it might lead to Kyoka’s work taking a more prominent place in Japan’s highly regarded literary canon.

[*Seidensticker translated Kyoka’s “A Tale of Three Who Were Blind” (1956) which appeared in Modern Japanese Literature (Grove Press, 1994), ed. Donald Keene.]

David is working on a novel set in Kanazawa. For an extract of the first chapter, see here: https://writersinkyoto.com/2016/07/novel-extract-david-joiner/