What was it like in Kyoto in the 1950s? You hardly ever saw foreigners, for one thing. If you did, you stopped to say hello. That was the Kyoto a banker from Holland called Hans Brinckmann got to know and love. Though he lived in Kobe, he visited whenver he could at weekends. As he got to know the town, he fell in love with it.

Hans Brinckmann arrived in Japan in 1950 to work in a bank in Kobe. He started learning Japanese despite the warnings of his sub manager that it would damage his mind. In 1954 he was transferred to Tokyo, where he missed his outings to Kyoto, so he was glad to get back to a post in Osaka. His favourite places included the bamboo grove in Imagumano Shrine; Tofukuji where he made friends with a monk who complained of ills from the rigorous regime of the Zen monastery; and a ryokan called Takeya, which he got to like despite the austerity of conditions there and the perishing cold.

Like others before him, he went though cultural conundrums about how to reconcile East and West, coming out on the Japanese side of things. The world was not simple black and white, right or wrong, as the Western ego insisted, but a more modest grey made up of maybe, sighs and silences.

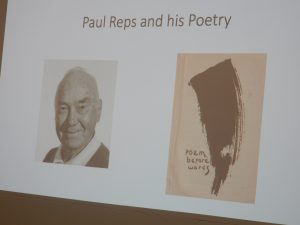

One key event was attending an exhibition by Paul Reps of Zen Flesh, Zen Bones fame. He had done wonderful freehand calligraphy of whimsical words on Japanese ‘washi’ paper. “Drinking a cup of tea, I stop the war,’ was one of the verses. Later Hans got to know him in his Ohara home. (Reps is now considered one of America’s first haiku poets.)

A more important friendship was with the poet Shimaoka Kenseki, who introduced him to all manner of artists, potters and monks. One of the most colourful was a poet and personality called Ichida Yae san, an heiress who wore her kimono in defiant mock Heian style and was known as the second Ono no Komachi for her beauty. She is said to have been the model for one of Tanizaki’s heroines.

Hans was closely involved in setting up Kyoto’s first Dutch restaurant, though alas it went out of business after two years. He also took part in the English edition of a Japanese poetry publication called New Japan Pebbles, but it too only survived six editions. All the while he enjoyed networking with Shimaoka, who was not only a poet, but a teacher and columnist with a wide range of friends – a gynecologist, an obi maker, a building contractor. One person Hans befriended was the potter, Katoh Sho, who dealt in tea ware.

But the most significant of the encounters in Kyoto came through an unexpected and unrequested omiai he had, with just two hours’ notice. It turned out the couple shared the same literary and pottery tastes, and when she happened to brush his arm he ‘flexed his banker’s biceps in acknowledgement’. The pair married and spent a happy life together until her death in 2007.

Hans has published many articles and books, covering poetry, fiction and non-fiction. Asked about his writing process, he said it was different for each genre. Fiction he could see unfurling in his imagination, non-fiction required constant fact checking. He confessed to being a slow writer, though the volume of publication would suggest he’s a hard worker.

And what does the great lover of Kyoto think of the city now? You hear more Chinese than Japanese in the streets, he says. It’s difficult to even recognise some of the areas. But notwithstanding he remains a strong admirer of the city and its people because of their modest dignity and pride in upholding tradition. For personal reasons Hans now lives in Fukuoka, but he still makes an effort to revisit the city he fell in love with all those years ago.

************

For a listing of Hans Brinckmann’s work, both in English and Japanese, take a look at this amazon page. Of particular note here is the collection of short stories, The Tomb in the Kyoto Hills.. For the website blog of Hans, with videos and his writings, see here.

Books by Hans Brinckmann (with thanks to Deep Kyoto)

The Magatama Doodle

Part personal memoir, part professional flashback, part socio-cultural commentary, this title chronicles the author’s experiences during his twenty-four years (1950-74) of living in Japan as a reluctant banker. It also touches on some of the significant changes that have taken place in Japanese society since the mid-Seventies.

Noon Elusive

An American architect in Paris, a Balkan parachutist, a Dutch diplomat in Japan, a New York heart surgeon, an English undertaker-the characters are as colourful as they are diverse. What they have in common is that they are all in the throes of personal crisis, mild and manageable, or severe and harrowing. Consciously or not, they are all in search of the high noon of life.

Showa Japan

Japan’s Showa era began in 1926 when Emperor Hirohito took the throne and ended on his death in 1989. The formative age of modern Japan, it was undoubtedly the most momentous, calamitous, successful and glamorous period in Japan’s recent history. Today, Showa is a beacon for nostalgia that is memorialized yearly in a national holiday. An era of growth and prosperity, it saw Japan go from an isolated, embattled nation to a peaceful country holding the exalted position of the world’s second largest economy.

The Undying DayA widowed water bird in an Amsterdam canal… abandoned villages ‘flitting fitfully by’ as he rides the Eurostar to Paris… the sun, ‘averse to setting, extending the you-filled day’… such are the diverse sources of inspiration for Brinckmann’s poetry.

Unconstrained by locale or subject matter, his lines celebrate the marvel of love and ponder life’s irretrievable losses. He is no stranger to whimsy either, nor to the search for life’s ultimate meaning.

The Tomb in the Kyoto Hills

A striking and highly engaging collection of stories. The offerings include A Leap into the Light, the compelling tale of a Dutch businessman’s secretive life with the young daughter of his late Japanese mistress; Kyoto Bus Stop, about the chance encounter between a visitor from Europe and a mysterious young French woman in Kyoto; Pets in Marriage, which chronicles a Japanese married couple and their respective preference for cats and dogs, which comes to a head at the foot of Mt. Fuji; Twice upon a Plum Tree, an exploration of a Dutch diplomat’s ambivalence about a Japanese woman he once loved; and the title story, The Tomb in the Kyoto Hills, about a Chicago-based lawyer who moves his family to Japan to find the truth of his origins once and for all.

In the Eyes of the Sun

Peter van Doorn, dreams of life with a camera. His leftwing father, Eduard – a journalist and former WWII photographer – at first supports his son’s ambition and even gives him his wartime Leica. But when Peter tries to save someone from a fatal accident instead of “capturing the moment of violent death,” Eduard decides that his son lacks the guts for “real” photography, the kind he practiced during the war, the only kind of photography “worthy of a man,” even in peacetime. He forces Peter into overseas banking instead. Starting in 1953, Peter’s exotic career takes him from his native Holland to Singapore and on to Chicago where he marries a socialite. But his dream never dies, and at last, in 1978, he sacrifices his stable career and family to embark on the life of a freelance photographer – in New York.