Interview with Marianne Kimura

Q. It was a fiercely hot summer in Kyoto, the ancient capital of Japan. How did you cope?

A. I stayed indoors in my air-conditioned bedroom and sat on my futon writing papers. First, I wrote about the goddess in As You Like It. The next paper was about how Hamlet is similar to a ninja.

Q. A goddess? Are you sure? No one talks about goddesses in Shakespeare usually.

A. I first discovered a goddess figure in Shakespeare on Halloween, a few minutes past midnight, last year. It was really quite spooky. I was doing an investigation of Love’s Labor’s Lost (written around 1595) and its original subtitle is “a pleasant conceited comedy” so I knew there was a conceit (an extended metaphor) there. I read the play carefully over a few days at the end of October when my college gave us a break from teaching classes for a student festival. I also watched the play on YouTube—a production with Jeremy Brett. It’s very well done. By October 30, I was finished reading it and that evening after dinner I started to try to think how any allegory or conceit was functioning. Finally, late in the evening I realized that there were all these images of and references to blindness, goddesses, sun worship, wounded deer, philosophy, the number nine, and pedants.

If you take all these elements together, and if you know the importance of Giordano Bruno to Shakespeare’s work, then all of these elements are found in only one book: Bruno’s Gli Heroici Furori (The Heroic Furies), which was published in London in 1585. I suddenly realized that Shakespeare had hidden the main ideas and elements of Gli Eroici Furori in this play. That is the conceit! I happened to check the time then and it was few minutes past midnight on the 31st: Halloween! I felt as though a ghost had dropped in to whisper the answer. Halloween, you probably know, is the day spirits are said to return, kind of like O-bon in Japan. I was happy but also I was sort of freaked out.

Q. What happened after that?

A. Well, I wrote the paper and it got a lot of views on Academia and also it got published in a journal of the college where I work. And I sent in the idea to the British Shakespeare Association which was organizing a conference to be held in June in Belfast and they accepted the idea and I got to go to the conference and present my idea. It was great fun.

Q. What do you mean by the Goddess?

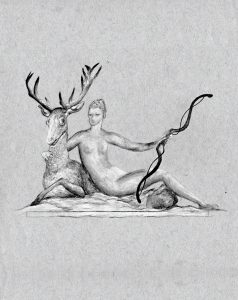

A. Bruno knew about goddesses in general but he also came up with his own specific vision in Gli Heroici Furori, which is an allegory too, because the Divine Feminine (also known as the Goddess) was a heretical idea in Bruno’s day of course. There are two supernatural characters in his work, one is the goddess Diana and one is a nymph in the River Thames. Each one stars in a little story in the book. In the first one, Actaeon, the hunter, is used as Bruno’s metaphor for the Heroic Lover, a philosopher in search of the Divine Truth. Well, he finds it, symbolized by Diana bathing in a pool under the moon. She sees him, of course and turns him into a stag, whereupon he is killed and devoured by his hunting dogs.

According to Bruno, the Heroic Lover then achieves his goal of finding the Divine Truth because he merges into nature, into the world, he becomes one with it and ceases to see himself as separated from it. This is pretty deep actually: this is the place where the material world becomes sacred because we see ourselves as one with it. This is a worldview that modern people associate with indigenous tribes who, of course, usually have goddesses. But to Bruno, this is the correct view. It’s very much an environmental idea too: don’t corrupt and pollute your planet because you corrupt and pollute your own body too.

Q. What about the nymph?

A. In this anecdote in Gli Eroici Furori, nine philosophers near Rome are struck blind by the witch Circe when she sprinkles water on them. Then she kindly gives them a sealed jar and says that if they can open it they can sprinkle the water inside it on themselves and see again. They are very upset since they can’t open the jar and though they are blind, they somehow wander all the way north through Europe and end up in London, near the River Thames. A river nymph there opens the jar easily and sprinkles the water on them. They can see. Some scholars see this nymph as Queen Elizabeth I, who was in power at the time. Scholars also see the nymph as representing learning, scientific scholarship, wisdom, knowledge and these things that were going against the superstition and closed-mindedness of the Catholic Church of that day.

I think what Bruno was trying to say was that a goddess should have two aspects: one (Diana) is the sacred beauty of nature, the other (the river nymph) is a positive mind for learning and education. He saw Europe as very much in need of such a goddess. And Shakespeare liked this idea tremendously too. To him, the Divine Feminine was obviously sacred. He put it into his works as much as possible. Of course he hid it; the idea was totally heretical. That’s why all the major female characters in the comedies are disguised in one way or another.

Q. Ah ha! So in As You Like It, Rosalind and Celia, who are dressed as men, are goddess figures.

A. Exactly! There is so much Brunian imagery in the play too: a wounded stag, a philosopher from the Continent, a magician hidden in the forest. Plus, the play is against capitalism and fossil fuels. Little words like “mines” show the hidden concerns Shakespeare had with coal. And he was completely correct to be concerned: fossil fuels (coal) were wrecking London in his day and now they (coal and oil) are wrecking the planet. Plastic pollution is a huge concern but climate change is another big problem. It was often too hot to go outside safely in Kyoto this summer and many other places around the world also reported record high temperatures. 2018 is one of the hottest years on record, surpassed only by the four most recent years preceding it. Scientists warn we will also see huge problems developing with agriculture with such hot temperatures. We need to phase them out a.s.a.p.

Q. What about the ninja and Hamlet then? That also sounds unconventional for a Shakespearean!

A. I was casually chatting about ninjas with one scholar I met in Ireland at the BSA conference. I’ve been studying ninjas for a while actually and I was explaining to him how ninjas use unconventional fighting techniques. A few days later, just daydreaming, I put the idea of Hamlet together with ninjas because I realized that Hamlet uses unconventional fighting techniques too. He waits a long time to strike and ninjas often also had to wait a long time.

The first kanji in ninja is 忍, which means shinobu, to bear or endure. Then I checked a book I have called the Shoninki (正忍記) which was originally written on scrolls in 1681 in code by a real ninja master named Masazumi Natori. The Shoninki is rare because mostly ninja instructions and educational material were orally transmitted to preserve the secrecy of the ninja strategies.

The Shoninki has a lot of specific advice for those who want to be ninjas. I compared this advice to some of the things Hamlet does and says and I found many similarities. I don’t mean that Hamlet was exactly a ninja, only that ninjutsu has some philosophical background in Taoism and Zen Buddhism and it’s possible that Shakespeare could have intuitively grasped some of the principles involved: for example the Way, the nebulous and profound idea from Chinese philosophy that touches on morality and other aspects of our fundamental connection to the universe.

Q. You found ninjas and goddesses in Shakespeare! Your views are very unusual indeed! How do you cope with being so unusual in your field?

A. I don’t really care. To me, Shakespeare and his works have more in common with the mad dashing world of Japanese manga and anime, (where indeed you can sometimes see ninjas and goddesses), than anything else. In manga we often see outsider, underdog, even sort of ridiculous characters up against overwhelmingly strong powers.

To me, Shakespeare was a mad (in a good way) dashing hero fighting secretly and valiantly for a bunch of outsider underdog causes: he was against capitalism, against fossil fuels, against monothesism, and he was for Giordano Bruno, for the Divine Feminine, for our planet, for sun worship and nature worship. He hid his real ideas in allegories; it’s like a secret code, another ninja-like aspect of him. It’s fantastic, heroic, brilliant, romantic. As an academic, I’m perfectly content to explore this aspect of him and I know that as long as I stick to this ideology, I’m necessarily an outsider, in exile, and an underdog myself in this world we live in now. I’m also extremely grateful to Japan for being a country with this wonderful culture that gave me a deep education in goddesses and ninjas—often, yes, I turned to anime and manga for information and inspiration. Also Shinto shrines and folktales. I think Shakespeare would have loved Japan.

Q. Lately, you’ve been focusing on non-fiction, your scholarly articles. How about more fiction?

A. Yes, maybe, I might try a third novel soon. I am trying to come up with some plot ideas. I want to explore this idea of the goddess a lot more. A novel with a goddess might be great fun. I only want to write something, non-fiction or fiction, if it’s great fun for me. That’s my only rule.