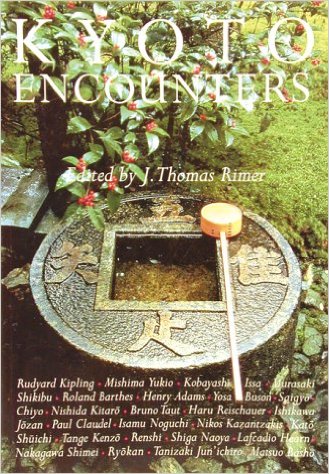

A literary stroll through the four seasons – Kyoto Encounters (1995) has to be one of the most attractive English-language collections ever produced about the city. Edited by J. Thomas Rimer (Professor Emeritus at Pittsburgh University and author of several books), it combines visual beauty in commissioned photos with extracts culled from the corpus of Japanese literature.

The book is also notable for the sensitivity of its layout, with pictures specially commissioned by the Bank of Kyoto for a ‘I love Kyoto’ campaign allowed space to speak for themselves. Rather than being limited to the city proper, they cover the whole of the prefecture which means the reader is often surprised by just what constitutes ‘Kyoto’ – pictures of the coastline for instance are not what one expects. The text which accompanies the photos are arranged so as to complement rather than intrude, with the employment of different font sizes to cope with the different types of extract. This encourages pieces to be read as intended by the author, with the larger print for haiku commanding careful consideration of each and every word.

For the most part there is one quotation per picture, and on occasion two. Surely only someone of Rimer’s erudition could have come up with such a comprehensive collection, culled not only from Japanese literature but from observations too by foreign visitors. The juxtapositions are felicitous, and in the manner of haiku the links are often oblique rather than explicit. Sometimes the match of prose and picture is pleasingly precise – a photo of snow-covered tiles is accompanied by an extract Sei Shonagon that might have been describing the very scene. This happy combination of past and present is one of the great rewards of Rimer’s foraging.

At other times the combinations leave one thinking; what for instance is the connection between the contemporary Jidai Matsuri and a sixteenth-century imperial procession? Or take the visit of Go-Shirakawa to Jako-in at Ohara, which is accompanied not by a photo of the temple as one might expect but a solitary farmhouse standing amongst Ohara’s rice fields, thereby emphasising the sense of rural isolation expressed in the extract.

When I was researching my book on Kyoto: A Cultural History, I was surprised to find how little English-language material there was in terms of literary portrayals. It means the challenge for Rimer in putting together nearly a hundred quotations was more formidable than it might appear, but the University of Maryland professor adopted an ingenious method to deal with the problem; since the photos already speak of Kyoto, he sought to address their subject-matter, meaning that some of the extracts very little to do with city or indeed prefecture. There are haiku by Kobayashi Issa, for instance, alongside the seaside fields of Niizaki. Or take Saigyo’s death-poem about wishing to die in cherry blossom time under a full moon: the poignant verse is set aside a stunning photograph of a cherry blossom branch against a hazy backdrop of the Nanzen-ji aqueduct. Though the original poem had nothing to do with Kyoto, Rimer has freed himself to combine the very best of Japanese literature with the visual appeal of the city. It means even afficionados of Kyoto will find exciting discoveries, for along with often quoted pieces such as those by Basho and Buson are less well-known verses such as this:

Ah, the dancing!

In Kyoto

So many women.

The haiku is by Renshi (1649-1742), and one of the great assets of Rimer’s book are the notes discretely tucked away at the back. These constitute a cultural miscellany in themselves, and from them we learn that Renshi carried on Basho’s haiku style after being trained by one of his disciples named Sugiyama Sanpu. Another verse that caught my attention, particularly as it accompanies a striking photo, is the following by Nakagawa Shimei, whom Rimer notes was a haiku poet of Meiji times concerned with the beauty of the seasons in Kyoto:

The first rainbow;

A girl selling flowers

Goes along the Shirakawa road.

Along with the Japanese writers are foreign commentators, such as the sixteenth-century Italian, Gaspar Vilela, and the twentieth-century German, Bruno Taut. Unexpected names like Nikos Kazantzakis mix with the well-known, such as Lafcadio Hearn. Together they chronicle the amazing transformation of Kyoto over the centuries. In 1931, for instance, Noguchi Isamu was able to remark of the city’s temples that ‘nobody ever went there’, and that ‘The legendary gardens were generally neglected, as were important architectural structures, many of which were rotting away.’ We learn too from Rimer’s extracts that the the lives of ordinary people too have dramatically changed, as noted by the wife of Edwin O. Reischauer: ‘Even as late as the 1940s it was a life of grinding poverty, but the farmers quietly accepted it with dignity and self-respect, treating one another with decorum and courtesy.’

The result is a wonderful tribute to Kyoto, and Rimer’s collection of words and photos, long out of print, surely deserves a higher profile. It remains one of the most stimulating and accessible books produced about the city (and its surrounds), with something of appeal to both visitor and resident alike. As we approach the festive season, it’s a miscellany that could well serve as an attractive Christmas present, even in secondhand form.

Thomas Rimer has written in to say:

“I have written a number of scholarly books on various aspects of Japanese

literature, theatre, and culture, but my two favorites were not academic

books at all, and both were about Kyoto. The first, SHISENDO which I wrote

together with a several colleagues, paid homage to one of my very favorite

places in Kyoto, as well as signalling my fascination with the productive

intertwining of Chinese and Japanese artistic and literary culture during

that period. The second was KYOTO ENCOUNTERS, which gave me a chance to

match some of my favorite Japanese authors, many of them related in some

fashion to Kyoto, with those remarkable photographs assembled for me by

the editors of Weatherhill. It was a grand opportunity to write something

about my favorite city, and for pure pleasure.

Unfortunately, Weatherhill exists no more; from what I understand, the

company was sold to Shambhala, a publisher of books on Buddhism and

related topics now located in Boston, Massachusetts. I don’t believe that

they have reissued many of the Weatherhill titles.

As I have not been able to travel to Kyoto for almost twenty years now, I

can only wonder how the city must have changed; I fear in particular for

the likely loss of my favorite Taisho-period coffee shop near Kyoto

University. But I certainly envy those of you who live there and can watch

the the seasons and the slow push of history move gently along. It’s a

rare privilege.