Cooling off by the River at Shijo (1690)

By Jeff Robbins, Compiler of the Basho4Now Trilogy

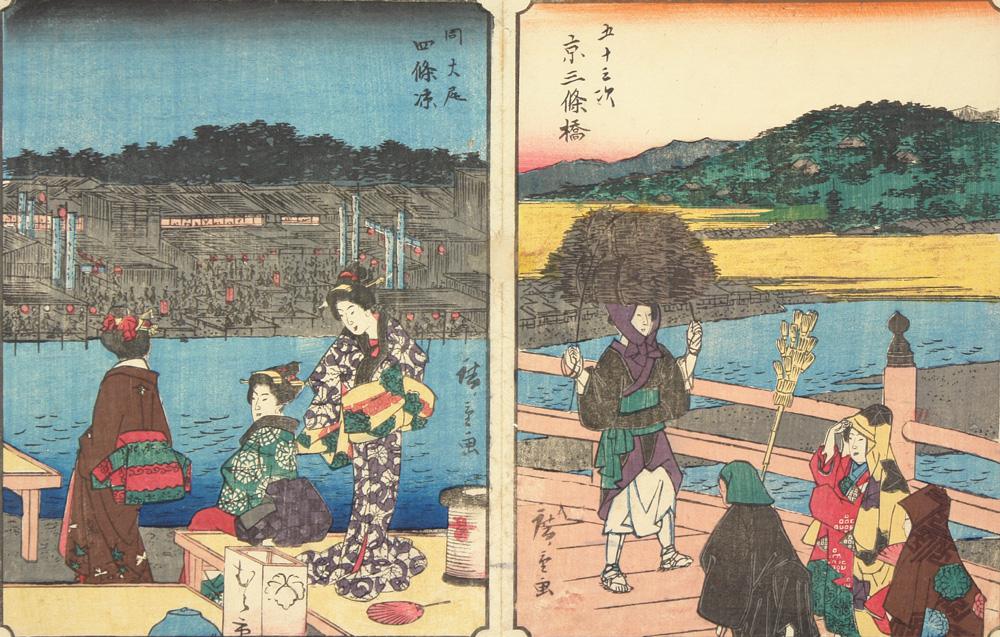

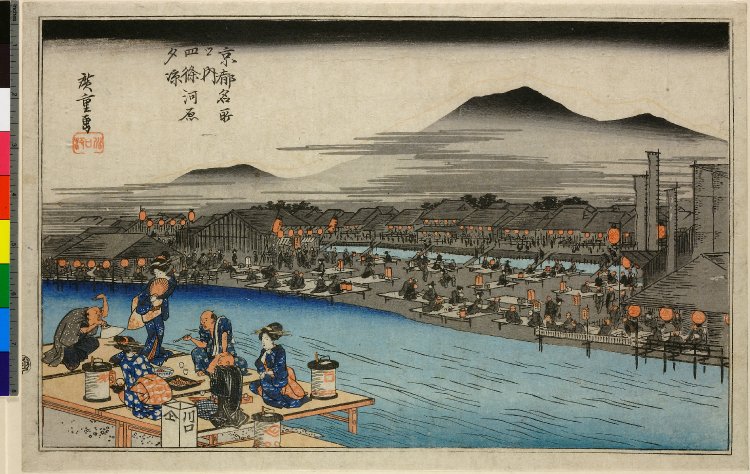

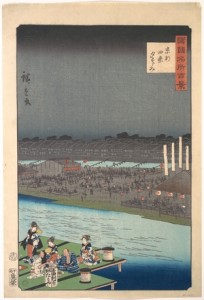

The custom Basho describes in the following haibun and haiku began in the late 12th century as part of the Gion Festival; a temporary bridge was set up for portable shrines to cross the Kamo River near Gion Shrine (now Yasaka shrine), and eventually tearooms proliferated at the foot of this bridge By Basho’s time in the late 17th century platforms were built over the river and people flocked there to enjoy the river coolness. There are famous paintings of “Cooling off by the River at Shijo” by both Ando Hiroshige (1835) and his son-in-law Ando Hiroshige II (1860).

The custom continued every summer until with the Sino-Japanese War and World War II it died out, being regarded as an indulgent luxury. It resumed in 1951 and continues to this day, between the Nijo Ohashi bridge and the Gojo Ohashi bridge on the west bank from May through September every year. John Dougill reports of the modern event: “When the full moon comes up behind the Eastern Hills and geisha sit out or walk past, then one can well see why it would capture the heart …”

In Basho’s time the custom was practiced from the 7th of the Moon when the moon set during the night until the 18th when it shone in the dawn sky. May I offer this haibun and haiku to the Kyoto Tourist Office for advertising summer in Kyoto?

Cooling off by the river at Shijo

is a custom from the time of the evening moon

till it passes through the dawn sky.

People line up on a platform over the river to pass

the night drinking, eating, and having a good time.

The women’s kimono sashes are extravagant,

the men’s haori jackets long in the formal style,

Buddhist priests mingle with old folks, and even

the blacksmith’s and bucket maker’s apprentices,

their faces smiling with leisure, sing loud rowdy songs.

It is a scene to be expected in Kyoto.

River breeze —

wearing pale persimmon

in evening cool

Basho, as a skillful journalist, uses human sensation – food and drink, color, sound — to bring us into the scene, so we enjoy the coolness too. Humanity and diversity are everywhere in the passage. The blacksmith and bucket maker keep their teenage apprentices busy every minute, so here the youths make the most of their night of freedom. Their counterparts today do the same.

The prose flows into the haiku. Someone at a party on a platform over the river elegantly wears a robe dyed with persimmon juice; that color expresses the rejuvenation we feel from coolness after a long hot day. The website Empower-yourself-with-color psychology.com says “The color orange radiates warmth and happiness…orange is optimistic and uplifting, rejuvenating our spirit… orange also stimulates the appetite… and promotes conversation and social interaction.” Good for parties!

The haiku is thus a superb example of Basho’s poetic ideal of Lightness: ordinary people enjoying themselves — without tragedy, loneliness or desolation (i.e. no hint of wabi-sabi). Basho provides only satisfying tactile sensation, invigorating color, and an appreciation for human life in summer.

Please send your comments to basho4now@mail.com