‘Mother of American Buddhism’; the first woman to be named abbot of a Zen subtemple; the first foreigner to become abbot of a subtemple; the compiler of important translations; mentor of Burton Watson, Philip Yampolsky and Gary Snyder; the mother-in-law of Alan Watts –– Ruth Fuller Sasaki (1892-1967) was by any measure a most remarkable person. She belongs among the very front rank of the pantheon of foreigners who have left their mark on the pages of Kyoto history.

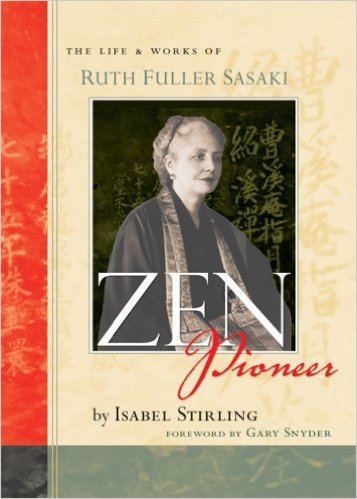

The story of her life is contained in the book, Zen Pioneer, written by Isabel Stirling with a Foreword by Gary Snyder. Her first marriage, to Edward Everett with whom she had a daughter, made her rich and gave her a wealth of connections. On their trip to Japan in 1930, she stayed at the Miyako Hotel and met D.T. Suzuki, who gave her a copy of Essays in Zen Buddhism (1927) together with advice about posture, breathing and mental techniques. When she returned the next year he introduced her to the head of Nanzen-ji. She practised meditation in a subtemple there every day from 9.00 am to 5.00 or 6.00 pm. Amazingly, as if that wasn’t enough, she did extra sessions in her house by the Kamo early in the morning and in the evenings.

On her third trip to Japan in 1933, she was ordained and ceremonially initiated into Buddhism. The next year she took her daughter, Eleanor, to study piano in London, where they met the young Alan Watts. (His marriage to Eleanor lasted 11 years from 1938-1949 and they had two children.) For much of the next decade she devoted herself to the Buddhist Society of America, run by Sokei-an Sasaki. Her husband had died in 1940, and four years later she married the ailing Sasaki, though the motivation is unclear (Alan Watts thought they were in love, though others suspected it was a convenient means to pass his name to her as next head of the institute). Before his death, in accord with his wishes, the institute was renamed The First Zen Institute of America.

In 1949, fearing that the Zen mission in the US might be lost, she went to Japan in search of a new teacher. She worked with the head of Daitoku-ji, who provided the use of a house in the temple grounds. Here she set up base and started sending back to the US authentic Zen sutra and furnishings. She also published articles and her long letters to the institute concerning Zen ways were disseminated and preserved.

The house in which Ruth Fuller Sasaki lived stood on the grounds of a former subtemple called Ryosen-an. In the years between 1955-60 she rebuilt the complex, putting up a store house for her Buddhist artifacts as well as a library-study and a zendo (meditation hall). She signed a twenty-year lease and developed the complex as an extension of the First Zen Institute in America. She had substantial back-up, including a couple of kitchen staff whom she trained in Western cooking. Illustrious visitors such as Joseph Campbell and R.H. Blyth often dropped in, as did several high-ranking Zen figures who enjoyed the ‘exotic’ food on offer.

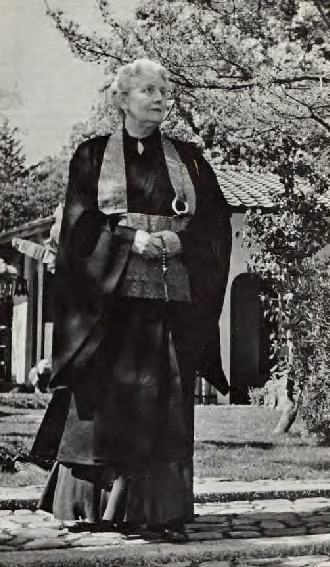

Part of Fuller Sasaki’s self-imposed mission was the translation of important Zen documents, and to this end she employed a team of researchers who included Japanese scholars as well as Burton Watson, Gary Snyder and Philip Yampolsky. (There was an acrimonious end when she sacked Yampolsky for allegedly planning his own translation, following which the others resigned in protest.) Then at the age of 66 she made history by being ordained a priest and installed as abbot of the restored Ryosen-an. There were about 80 people in attendance, and the event was featured in a Time article. Meanwhile she continued to write essays about Zen life, and four of her pamphlets were published in 1958-59.

She was apparently a woman of strong character and old-fashioned tastes, who disapproved for instance of Kerouac’s innovative work Dharma Bums (1958): ‘His Buddhism is the most garbled and mistaken I have read in many a day,’ she wrote. Yet when Allen Ginsberg came to visit in 1963, they got on well and had an engaging conversation about Howl. In 1967, aged 74, she died at the home she had created for herself at Ryosen-an, and in his Foreword for the book Zen Pioneer Gary Snyder provides a pen-portrait, drawing on his time working in her research team from 1956 to 1961…

Ruth Sasaki was in her sixties when I started working with her. She spent her days in elegant casual wear – many cashmere sweaters. Her hair and grooming were perfect, finished with pearl earrings. She started the mornings with a walk and sometimes an interview with her roshi. Then she might go to her study and review her literary Chinese-language readings, addressing translation problems from the text at hand. Much of the time it was the Rinzai-roku, or The Record of Lin-chi. She carried herself with imperious and matronly grace, and during her workday spoke with the cheerful and mannerly confidence that brooks little dissent. On issues of meaning in medieval Chinese, she was particularly stubborn…

Ruth had guests for dinner several nights a week. Dining was in a tatami room. Ruth poured martinis. She loved conversation, and after work hours enjoyed joining in a free-flowing debate. She had read widely in philosophy and literature, and could hold her own with almost anyone. Still, on some issues she was (I thought) extremely conservative and would not give way. One time she commented that most of the modern world’s problems started with Woodrow Wilson’s idea of ‘the self-determination of nations.’

She labored as though her vision held the only possible path that could take genuine Zen to the West… Her little booklets, in particular Zen: A Religion, were written in response to those who might hope to set aside ‘Buddhism’ and treat Zen as a secular psychological method of aesthetics, or self-help. Her writings from the sixties were ahead of their time and remain accurate and relevant… She thought of herself as a scholar-translator-facilitator and apparently never aspired to be a formal master. Her task was to prepare the way for those non-Asians who would eventually do full-scale traditional Rinzai-style koan study.

The Ryosen-an sub-temple (Tel: 075 411 0543) continues to hold early morning zazen (Zen meditation) sittings from 7.00-8.00.